A Brief Weekly Review, then on to What's Missing

Poultry outbreaks and California dairy cases accumulate, first severe U.S. human H5N1 case, and cats keep dying

Once again Dr. Kay Russo with RSM Consulting LLC has summarized “just the facts” quite succinctly in 2 LinkedIn posts on Thursday:

Kay Russo Post 1 | Feed | LinkedIn

Kay Russo Post 2 | Feed | LinkedIn

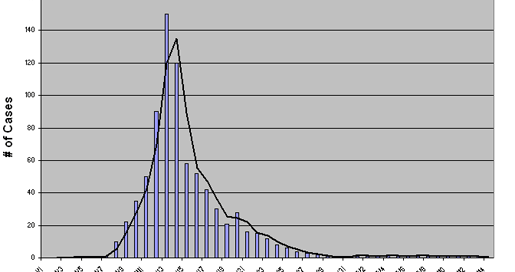

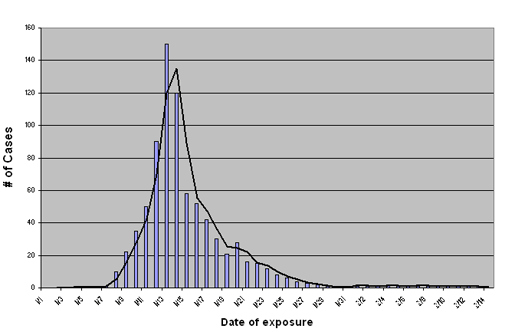

In the “old days” I could have devoted several paragraphs of comments to any of her bullet points in either post. None of us have the bandwidth anymore to write or read that much! We can look at H5 “events” as a type of epidemic curve:

Here is the first article I’d like to dwell on a bit more this week:

The really interesting piece of this announcement relates to the 3 “indoors only” cats diagnosed with H5N1 and NOT fed raw milk. As in Colorado last summer, we seem to have cases where cats are acting as sentinels for unknown viral encroachments into our environment. Once H5N1 establishes itself in an area, it seems to ooze out into multiple species and environmental samples.

For this particular case (and all positive H5N1 cases), it’s critical for the public health investigators to first establish the viral genotype that infected the house cats. D1.X would lean towards environmental contamination directly from wild bird migrations, unless the state animal health officials have recent evidence of nearby poultry or dairy infections with that strain. A B3.13 strain would imply some sort of direct or indirect cattle or poultry link, including the possibility of a meat source as pointed out in the press release. While “meat” is definitely a long shot, recall that a recent FSIS pilot program test found H5N1 B3.13 in a “healthy” cow sent to slaughter. It’s also possible that another meat species (pig, sheep, goat, etc., including early-infected asymptomatic poultry could have been fed to the cats. More likely sources of infection include fomites, humans, rodents, birds, etc. Once again, further investigations must start with sequencing, location, and careful histories in tracking down possibilities for disease transmission.

As I stated last week, companion animal veterinarians in California and elsewhere must raise H5N1 on their differential diagnostics list for upper respiratory infections, central nervous system disturbances, and sudden deaths, especially in cats, but also in other small mammals. Rapid H5 and influenza matrix gene lateral flow tests should be close by for initial screening in high-risk areas for rule-ins but not rule-outs. As this reported case shows, lack of raw milk consumption does not eliminate H5N1 as a differential diagnosis in high-risk areas! It’s critical for pet caretakers to be informed of the possible diagnosis at the first signs of illness to minimize their exposure risks and obtain early medical advice if their pets are provisionally positive.

With the continued surge in dairy herd infections, reported human infections in farm workers, the reported and suspected human case(s) without animal contact in Alameda County, positive raw milk farms, and record poultry losses from HPAI: Governor Newsom takes proactive action to strengthen robust state response to Bird Flu | Governor of California

On the same day of Governor Newsom’s announcement, CDC issued this: CDC Confirms First Severe Case of H5N1 Bird Flu in the United States | CDC Newsroom

A follow-up article in Forbes magazine featured commentary from several experts related to these 2 developments, as well the state of the outbreak in general:

The disclosure of a severe case of H5N1 renewed calls by experts for a dramatic increase in testing and reporting in the U.S. For months, researchers have warned that the bird flu outbreak was going to become a national issue, and they’ve worried that the virus could mutate in ways that eventually make human-to-human transmission possible.

Scott Hensley, a viral immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, noted that the Louisiana patient was infected with the same H5N1 genotype as a previous patient in British Columbia.

“It is possible that this particular virus has a greater potential to adapt and cause severe disease in humans,” Hensley says. The immunologist says he is “anxiously awaiting the sequence data from the Louisiana patient to see if there are genetic signatures of human adaptation.”

CDC declined to comment on Thursday regarding any similarities between the British Columbia case / virus and the Louisiana case, and sequencing has not yet been completed and deposited by CDC. Louisiana has declined to provide further details regarding the patient beyond that he is a 65-year-old+ “immunocompromised” male who handled backyard poultry and became infected with H5N1 HPAI. He is reportedly hospitalized in the Lake Charles LA area. NVSL on December 18th reported a positive backyard flock in Jefferson Davis Parish Louisiana.

While both the British Columbia, Canada, and Louisiana patient became severely ill, it’s important to note that many other people infected with H5N1 2.3.4.4b D1.X viruses have NOT suffered severe illness. These 2 patients are the exception to date, not the rule. That’s another reason why genomic analyses of these two viruses and close analyses of the case histories of these patients are of such importance. Additionally, there has been no evidence to date in either case of onward viral transmission, a key reason why CDC states that the threat level remains low.

We should have a better picture of the viral genome of the Louisiana patient by Christmas, with some educated opinions as to the significance (or not) of any SNP mutations in the 8 genomic segments that might make it more pathogenic. The LA County Public Health Department may be able to tell us whether the 3 house cats were infected by B3.13 or D1.X, perhaps with more information on possible routes of infection or risk analysis based on that sequence and further case investigations.

I continue to have tremendous sympathy for dairy farmers and their veterinarians who have endured ongoing reassurance from USDA and dairy industry representatives that “good biosecurity” related to lactating cow movements and fomites will prevent their herds from being infected. Megan Molteni with STAT authored an article on Friday, headlining the obvious:

“While some farmers may have been less strict” in following USDA precautions to prevent the spread of H5N1, “I personally know a fair number of producers that pulled out all the stops, followed every suggestion, came up with novel protections of their own,” Mike Payne, a food animal veterinarian and biosecurity expert with the University of California, Davis’ Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, told STAT in an email. “They still got infected and were enormously disheartened and frustrated.” ...In Colorado, for instance, H5N1 went through 74% of the state’s herds before it began to peter out. Payne believes that even with all the measures California farmers are taking, the virus won’t slow down until it has infected 80% to 90% of the state’s herds.

Route and extent of spread of both H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 and D1.X in all dairy and beef cattle and other domestic livestock are a big black hole at this point! We know about viral spread and spillover into poultry and cats because they die! We know about lactating dairy cattle because we’ve begun to require testing of bulk tanks and reporting of clinical signs when they occur. We’re conducting some ad hoc surveillance in wildlife surrounding poultry flock and diagnosed lactating dairy herd infections. We may accidently find it in other species if infected animals happen to show up in a diagnostic lab submission.

H5N1 is a reportable lethal disease in poultry flocks and a serious zoonotic threat for humans. However, the agricultural establishment neglects to conduct active surveillance of any sort in non-lactating cattle, other ruminants or swine, even in high-risk areas with active viral outbreaks in lactating dairy herds and/or poultry flocks. We don’t even test non-lactating cattle or other species on infected dairy farms or other livestock species on poultry farms for infected farm viral spillover to non-host species.

I’ve worked in regulatory medicine and heard the admonition to “stay within our authorities.” While I respect that concern, is anyone really considering the overriding consequences? At this point H5N1 is a partially mammalian-adapted lethal avian virus, easily transmissible between multiple species to an extent we don’t yet understand. It doesn’t read the 9 CFR but takes advantage of us when we use existing regulations to artificially limit how we respond to it.

Commodity groups and animal health regulatory authorities are trying to avoid exposure to reputational and financial risks by avoiding wider surveillance and research into the scope of H5N1 2.3.4.4b penetration into our domestic livestock herds. However, delaying the inevitable does not change it but only complicates dealing with the response required. Meanwhile, poultry, housecats, and peridomestic species sentinels keep dying.

Targeted PCR and serological tools can begin to unravel questions regarding the full host range and prevalence of H5N1 genotypes in our livestock species; however, USDA has to relax testing confirmation and reportability restrictions to encourage independent research and testing. Export issues may arise, but transparency is an ideal we must hold to, regardless.

I almost scrapped this nearly completed blog due to fast moving events Friday night-Saturday. I have decided instead to post this and send an update later today or tomorrow to discuss a couple of late-breaking cases that I believe may reshape the H5N1 paradigm.

Back soon with more, as attention turns from milk to meat…

John