A Quick Follow-up Before a Week Off

Lena Wen of the Washington Post nicely summarizes H5N1 today - I add some ag-related comments before signing off for a week

Opinion | Worry over bird flu is spreading in the U.S. - The Washington Post

Leana Wen is a public health columnist with the Washington Post. In this article she nicely captures several of the recent pieces of information released regarding new developments on the H5N1 front.

I found her closing paragraphs, including comments from Nicole Lurie quite powerful:

Nicole Lurie, the U.S. director for the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, told me that if this horrific hypothetical occurred, it would take a long time to find out. “Our system for looking is so poor,” she said, “we would be, in many respects, in catch-up mode.”

Lurie, who for eight years oversaw health emergency response during the Obama administration, thinks the government needs to make rapid tests for H5N1 available. “I certainly don’t want to have the availability or accuracy of rapid tests to be the single point of failure,” she said.

I agree. Rapid tests would help clinicians caring for farmworkers and their families. More testing would provide a better picture of how widespread this virus already is. Lurie also thinks health officials should provide avian flu vaccinations to at-risk populations. This would help protect them and yield data on vaccine effectiveness before broader deployment.

“We haven’t, in my mind, been thoughtful enough about laying out the series of steps to prevent broad introduction of H5N1 into the population,” she said. Federal leaders should heed her warning before the window to take proactive steps closes.

These comments are directed at the potential human pandemic response, but they apply equally well to our lack of rapid and flexible responses on the animal side. Refer back to my comments yesterday on the critical need for widespread surveillance in at-risk swine populations. Let’s ask ourselves how many deployable rapid tests for H5N1 we have available in veterinary clinics in California right now for cows? Cats? Birds? Pigs? We don’t do rapid! We do FADI’s, which require case assessment, communications with animal health officials, deployment, official investigations, and finally shipment of samples to a NAHLN lab for initial screening and presumptive diagnosis. 1-4 days later, we get confirmation and reporting of results from the national lab.

These are human constraints we put on our rapid diagnostic processes to assure accuracy and information control. Do we fully understand the price that these diagnostic constraints are putting on our rapid response capabilities? The same constraints we put in place to prevent “producer screening” for reportable diseases also prevent more widespread agile early detection! How many lives did this need for control cost us with lack of testing capacity for COVID19, all because CDC-FDA refused to open up alternative testing assays and capacity to lab use? Are we repeating the same mistakes with an extremely closed testing process for H5N1 in multiple livestock species? Who are we really attempting to insulate from harmful effects? The public, or special trade interests and a monopolistic diagnostic system?

On a somewhat related topic, I want to return to a pet peeve of mine, which is transparency in releasing genotypes of HPAI isolates in poultry outbreaks. I’ve been critical of NVSL for not more quickly making this information available; however, 1) it takes time to curate detailed and accurate sequence information; and 2) it may be that state veterinarians submitting samples do not wish to have data from their states released for political or stakeholder relationship reasons within their states. So rather than calling on NVSL to release that information, it may be more appropriate to ask that state veterinarians make those announcements based on local decisions.

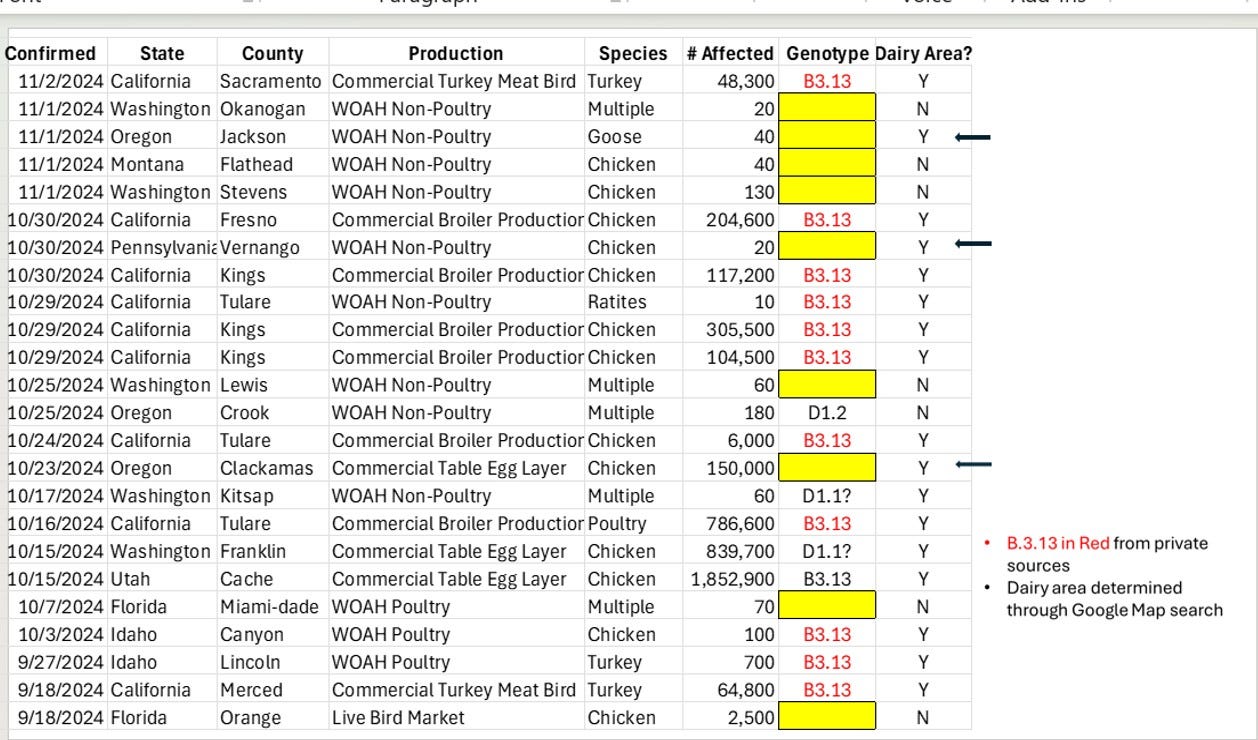

Regardless of who is the decision-maker, I still feel strongly that it is in everyone’s best interest for full transparency on genotype transparency, particularly related to outbreaks in poultry caused by the B3.13 strain in states not yet reporting infections in dairy herds. Here is a table of the recent HPAI outbreaks, which have really picked up since September 15th. Many are in California, which we have learned from private sources are due to B3.13. That is fully expected, given the widespread dairy outbreak in that state:

The Utah case was disclosed by the state veterinarian, Dr. Christensen, to be caused by the B3.13 strain which led to bulk tank testing in the county of the infected poultry flock and subsequent discovery of 8 infected dairy herds.

Note on the table that 1 Pennsylvania and 2 Oregon outbreaks have occurred in counties with multiple dairy operations in place as shown by Google Maps. This does not mean that those are B3.13 outbreaks! However, it would be reassuring if the state veterinarians in both states would publicly provide genotypes of the outbreak strains in those three cases. If B3.13, then dairy herd bulk testing might be considered, similar to what was done in Utah and in Iowa last summer. Worker monitoring and temporary animal movement restrictions on those dairy farms would be important additional considerations if positive.

If it is not B3.13, that is important to know also! I’d hope as we proceed into the fall with likely additional H5N1 poultry outbreaks, that genotype transparency will become a standard part of reporting as sequencing is made available. It’s a critical piece of epidemiological information for one health investigators and the public at large.

I leave early tomorrow for a week of time off with family in California (LA area). I’ll have my phone and computer but don’t plan to post regularly unless “the earth moves” again. (I guess in California I should never joke about the earth moving!)

Stay well and optimistic! We’re all good people at heart. No matter who wins tonight, my parents had 2 pieces of priceless advice when the stakes seemed high:

the sun will rise tomorrow

wait and see

John