August Recess- No New H5N1 Dairy Cases This Week or Commercial Poultry Cases This Month!

Using the lull to explore the role of human grief in explaining animal production industry and health regulators initial under-responses to emerging zoonotic disease threats

It’s the dog days of summer as vacations are wrapping up (even for reporters and researchers perhaps?), and emerging/zoonotic disease news is slow. The crush of bad news related to H5N1 in dairy cattle, poultry, humans, and even in cats from Colorado has abated as the virus likely burns itself out in the northeast part of the state. No epidemic of bad news and dire consequences lasts forever because a virus requires a constant supply of new “victims” to sustain itself.

I want to reflect this week on “preparedness” and why, for all the effort we put into white papers, advanced technology, and action plans to put us ahead of the curve for the next big challenge, we continue to fall woefully behind the curve when it arrives. I’ve been through a series of novel “outbreaks” in my long career, and they all tend to follow a similar script from the affected industry and government decision-makers, in large part, I’d argue, due to natural human emotions to the threats they bring. Examples from my experience include pmH1N1(09) in swine and humans, PEDV in swine, SARS-CoV-2 in people and assorted animals, and now H1N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 in dairy cattle (and beyond).

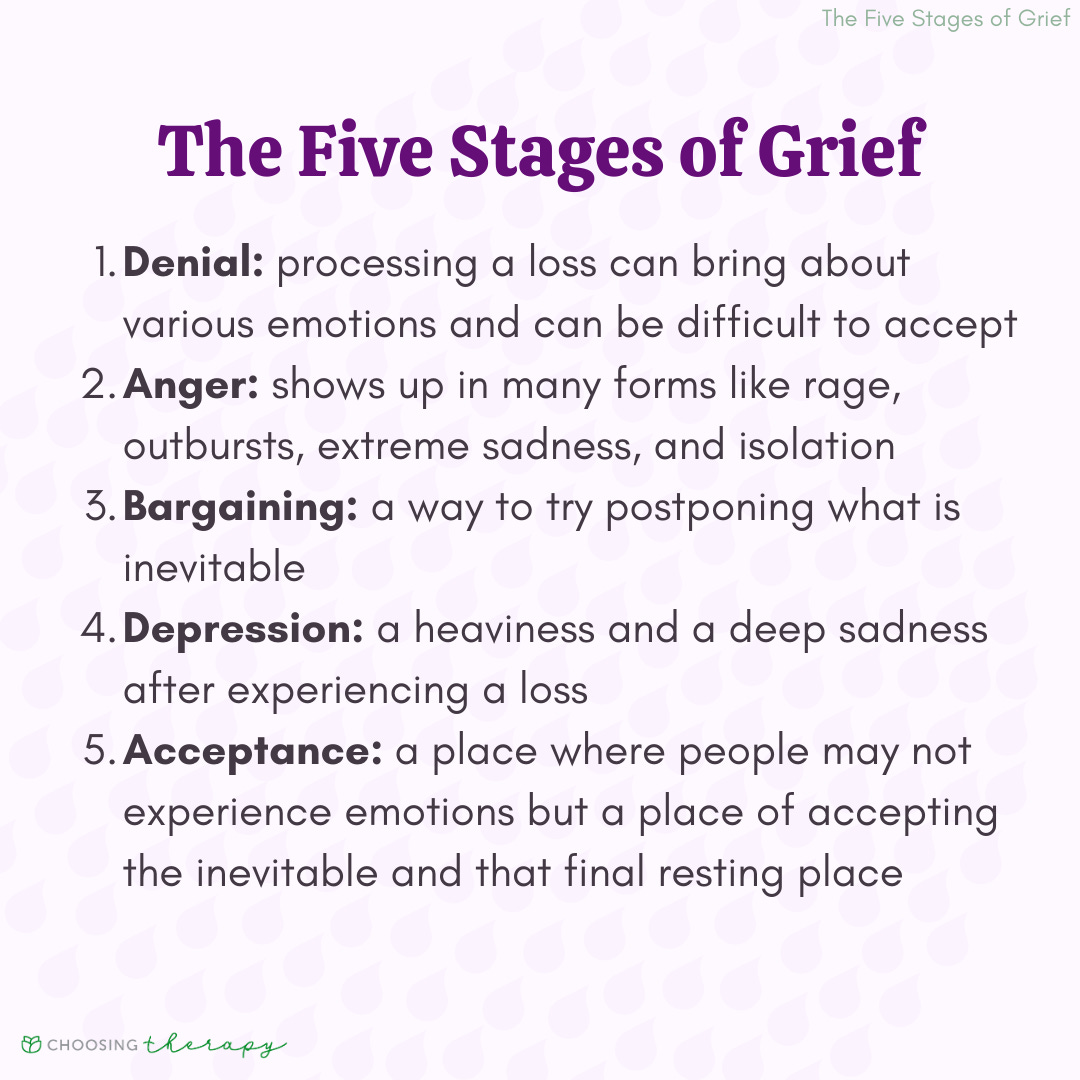

I propose that the arrival of an unexpected disease challenge for a major industry compares with a major loss or threat in life, inducing a classic grief response by that industry and its state and federal regulators:

In all of our readiness and planning materials for emerging disease outbreaks we seem to blithely assume that industry participants and response planners see the “facts” and threats of the outbreak for what they are; however, the bulk of any industry and most state and federal decision-makers are solidly in denial! Most plans I’ve reviewed ignore or minimize meeting the stakeholders where they will be, including all of the senior decision-makers, who are just as subject to emotional bias as everyone else.

As an outbreak typically unfolds, zoonotic / emerging disease subject matter experts are in their cubicles writing action plans for rational next steps that few strategic level decision-makers in either industry or their state/federal regulators are ready to consider. Most likely, industry leaders are on the phone or in person with USDA and State Animal Health leaders discussing “communications plans” heavy in denial that any actions are even needed (Your food is safe!) and emphasizing that the situation is of limited scope, limited actual risk, and under control through “state of the art” biosecurity programs.

The denial, anger, and bargaining phases can continue for months as palatable but semi-effective at best response activities are negotiated and funded to broker competing stakeholders demands. As One Health has come to the fore in the past 15 years, zoonotic emerging disease threats (pmH1N1(09), SARS-CoV-2, and H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13) have forced agricultural interests into more response, surveillance, and transparency than in the past, but this has not been a natural or easy adaptation for ag stakeholders who value anonymity. Furthermore, existing legal and regulatory authority in the U.S. is neither sufficient nor sufficiently enforced to actually develop the high level one health joint action surveillance plans envisioned in so many white papers and put forth as blueprints for future improved response processes.

It seems to me that the current dairy H5N1 situation has once again brought a valuable lesson in One Health regarding just how much collaboration we can reasonably expect from commodity groups and agricultural regulators when we develop joint early detection and response plans. We cannot expect people to overcome grief, a natural human response to adversity, with its attendant denial and anger, when their livelihoods are threatened.

Improved One Health action plans need to be devised that take into account the natural reactions of the people on the animal production side of the equation. That solution likely goes well beyond more financial support for producers, although that is part of the issue. The solution must also include some sort of independent One Health assessment input for ag industry decision-makers regarding acceptable minimal standards for dealing with undeniable threats to public health in the face of initial denial by animal industry stakeholders. While upper leadership will always make final decisions, I’d hope that they would respect and utilize approved plans that include multi-agency minimal standards for acceptable data and sample collection standards.

I’m not privy to how decisions were and continue to be made regarding H5N1 in cattle response at USDA. However, this seems to be the most centrally driven response yet compared to earlier outbreaks. Nearly all comments and statements have come directly from the Whitten Building with APHIS-VS, WS, and ARS having very subsidiary roles with carefully crafted support. The central message remains that H5N1 in dairy cattle is a milk-mediated mastitis, spread within and between herds by human controllable biosecurity breakdowns, perhaps with a minor, non-transmissible respiratory component. Onward infection is controllable through quarantine of actively infected lactating herds, combined with increased biosecurity to prevent spread from actively infected to non-infected herds by fomites contaminated by virus-laden milk.

As I’ve pointed out in multiple columns, I have issues with this message, as do many others. I suspect that even many within USDA may have information at odds with the message; however, the current agency culture is not conducive to free and open exchange within the agency or among agency-funded entities. Furthermore, the dairy industry continues to discourage sharing of information and on-farm research that would dispel the prevailing USDA message. There is undoubtedly sufficient information found in the heads of a variety of researchers, veterinarians and consultants that if consolidated, would move the industry much closer to understanding how this virus behaves both in a herd and across the industry. However, currently the critical mass of the industry seems to be content with plugging the USDA line as its message.

Back to public health (one health) it’s critical to monitor the H5N1 virus in dairy herds on an ongoing basis; however, that may need to be done on a pooled non-herd-specific basis through retail products and wastewater monitoring, or perhaps through other off-site environmental or product monitoring if proven useful and legal. Worker safety and monitoring is also critical, but lighter touches through localized outreach efforts may be more effective over time to reach workers and family members as human symptoms develop, not as part of post herd outbreaks when human viral RNA has likely already cleared.

If the USDA position on the nature of the outbreak is correct, caseloads will continue to decline in dairy cattle in the months ahead, with a few setbacks. The Colorado weekly bulk tank testing should show continued progress towards fewer or no new or re-outbreaks. Any new poultry outbreaks should be traceable to likely wildlife or wild bird incursions, rather than nearby dairy herd outbreaks. And reports of dairy worker H5N1 infections will cease. Finally, any H5 wastewater hits should be explainable by wildlife drainage into sewer sheds, rather than milk processing facilities in dairy dense states. The virus will still be present in the environment as a threat for reinfection, but dairy herds can remain uninfected though good biosecurity.

On the other hand, weather will turn cooler adding to stress, cattle will be moving to winter locations or between herds, and dairy cattle returning from fairs will be home long enough to incubate possible new herd outbreaks, if non-lactating H5 infections are real. Wildlife will be on the move seeking shelter, to whatever extent they may be responsible for carrying infection between sites. In this scenario, the caseloads may resume, leading to related poultry outbreaks and ongoing reports of worker illness.

We are about to test the USDA versus systemic/ endemic H5 infection hypothesis. As much as I have personally invested in my arguments regarding the underlying systemic dynamics of this infection, I would grant that the USDA position is the least painful way out for everyone! Knowledge of this outbreak will be 8 months old by October 1st. I’m betting we’ll develop a lot more consensus between all the parties by then with further research results, more case experience, and 2 more months for the industry to adapt to the change that H5N1 has brought to it.

Human emotions such as shock, denial and anger play prominent roles in initial phases of a developing zoonotic threat within animal production industries and the state and federal agencies that represent their interests. Future plans must strive to work around and with those emotions, not push through them, assuming collaborative approaches right up front. We are soon 6 months into the H5N1 outbreak in dairy cattle and at best, we have segments of the dairy industry rationalizing and bargaining, while many folks are still in denial and anger. It’s a very human process, and we should not expect a different response. Grief never fully resolves for those affected, but we all learn to move into the new realities of the world we live in, which now includes the mammalian H5N1 2.3.4.4b “dairy” clade.

John