California H5N1 Dairy Outbreak Explodes - Time to Talk Feral and Outdoor Swine Risk

Dairy and poultry are a serious workload issue now; however, swine may be the bigger zoonotic risk that must be monitored in a state with ample swine spillover potential

The H5N1 dairy herd outbreaks in California continue to build almost exponentially, as covered Friday by an article in the LA Times: ‘More serious than we had hoped’: Bird flu deaths mount among California dairy cows

The count at NVSL now stands at 56 dairy herds, although the total number of confirmed and presumptive positive cases was rumored to be closer to 100 herds at the end of the week. Additionally, a third positive human H5N1 conjunctivitis case was confirmed by CDC on Saturday. Both cattle and human cases will likely continue to build in the coming weeks. With the ongoing intensification of the H5N1 viral load in the Central Valley in the dairy herds, I would expect further pressure on poultry flocks as well as in domestic cats and peri-domestic species; we will likely see positive findings in multiple species similar to what was experienced in Colorado in late summer.

Unfortunately, California is also home to a robust feral pig population and significant outdoor and show pig farms, some closely adjoining the concentrated Central Valley “dairy belt”. Many influenza experts are concerned about enhanced zoonotic potential for H5N1 viruses that might spill over and establish ongoing infections in swine populations. Swine already endemically carry many human spillover H1 and H3 viruses, and pigs are prone to easily reassort viral segments when co-infected with 2 viral strains. This potential reassortment between a mammalian-adapted H5N1 and swine-human H1-H3 / N1-N2 endemic viruses in commercial production swine is a potential shortcut to a fully adapted H5 human pandemic strain.

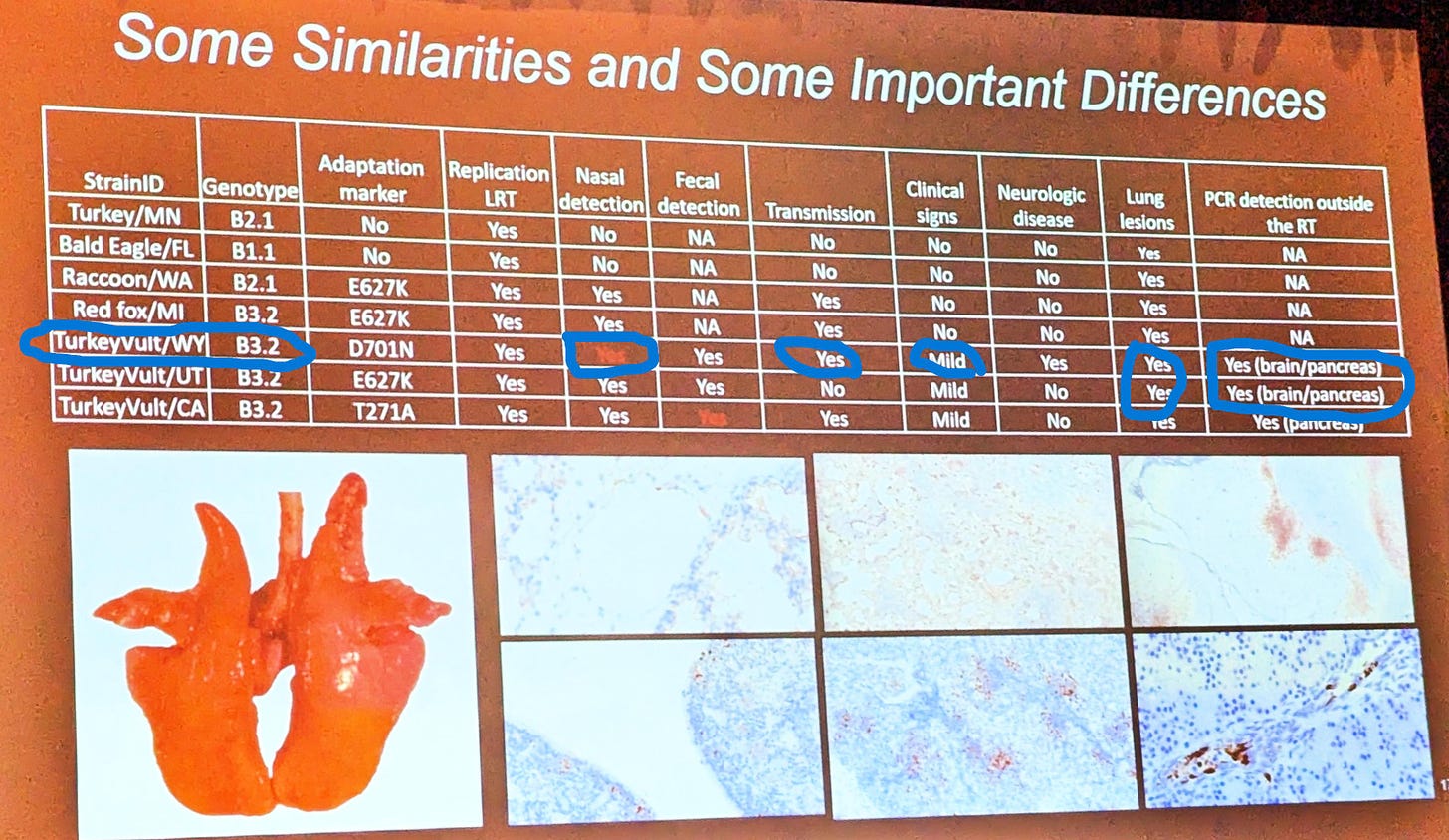

Dr. Bailey Arruda with the National Animal Disease Center (ARS) in Ames, IA, presented their research findings to date and future plans for H5N1 infection studies in pigs at the Leman Swine Conference 2 weeks ago. H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 (dairy) clade has not yet been directly placed in pigs; however, NADC had earlier in 2024 placed 4 partially mammalian-adapted H5N1 viruses in pigs in BSL-3 facilities. This photo of a slide in her presentation provides a summary of the findings:

There were differences between the strains (B2.1 and B3.2) and the species from which each virus was isolated. Unfortunately, the dairy cow outbreak unfolded as this work was completed last spring, tying up researchers’ time on high(er) priority cattle transmission studies. This has prevented this work from being published.

Perhaps the most concerning isolate findings to me in this unpublished work are from the Wyoming turkey vulture B3.2 strain. It was shown to:

produce mild clinical signs, including neurologic signs

be detected in nasal swabs, feces, brain, and pancreas, indicating systemic infection

replicate and produce lesions in the lungs

transmit onward to contact pigs

Perhaps more concerning, this premier swine lab has been delayed in infecting pigs with H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 in a timely fashion that would provide critical data on how this now highly prevalent virus behaves and transmits (or not) when placed into susceptible pigs. Lack of USDA leadership in marshalling a more inclusive, truly collaborative multi-institutional effort to understand H5 in cattle has had real costs in swine industry preparedness for possible H5N1 spillover events in feral or domestic swine.

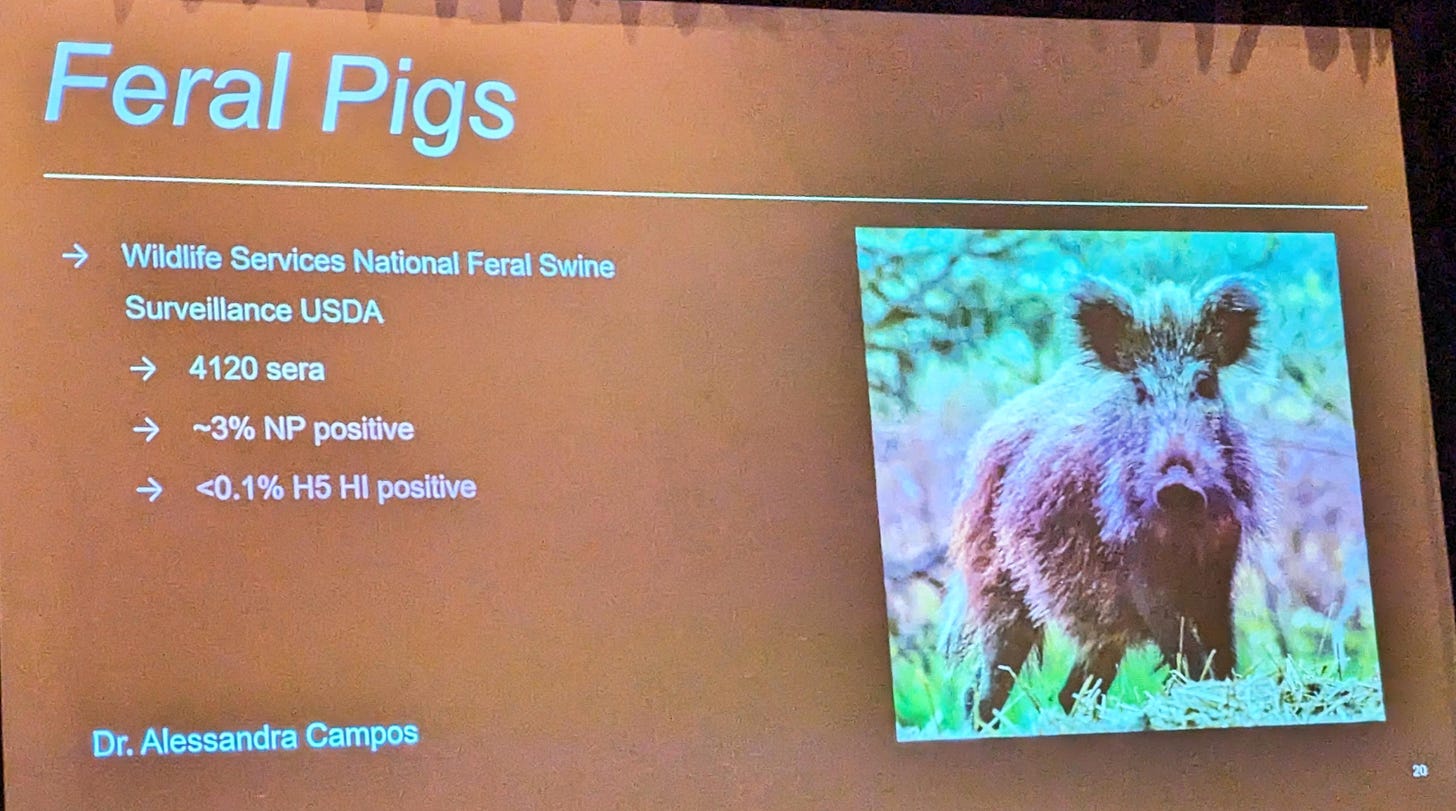

Despite testing assay knowledge gaps, ARS is currently funding a feral swine H5N1 surveillance project with a goal of testing about 8000 serum samples collected by Wildlife Services harvests for H5 antibodies. Dr. Arruda presented the following results to date:

While 3% are NP positive, these likely includes pigs seropositive from H1 and H3 endemic infections. These samples are then tested via H5 Hemagglutination Inhibition (HI) testing at NVSL; the data shown would indicate that 4 animals have shown positive titers. While it’s possible or perhaps even likely that these pigs may have been exposed to H5 B3.13, that cannot be determined with certainty, given that other high path and low path H5’s also may exist in the environment and diets of feral pigs and cause HI cross-reactions. Without serum from known infected pigs to evaluate seroconversion properties (positive controls), it’s difficult to interpret the significance of these findings.

ARS and Wildlife Services recently began sampling a subset of harvested feral swine for H5N1 virus antigen by PCR sampling of nasal swabs. I assume all tested to date have been negative, since any positive findings would require immediate reporting to WOAH and make animal health headlines.

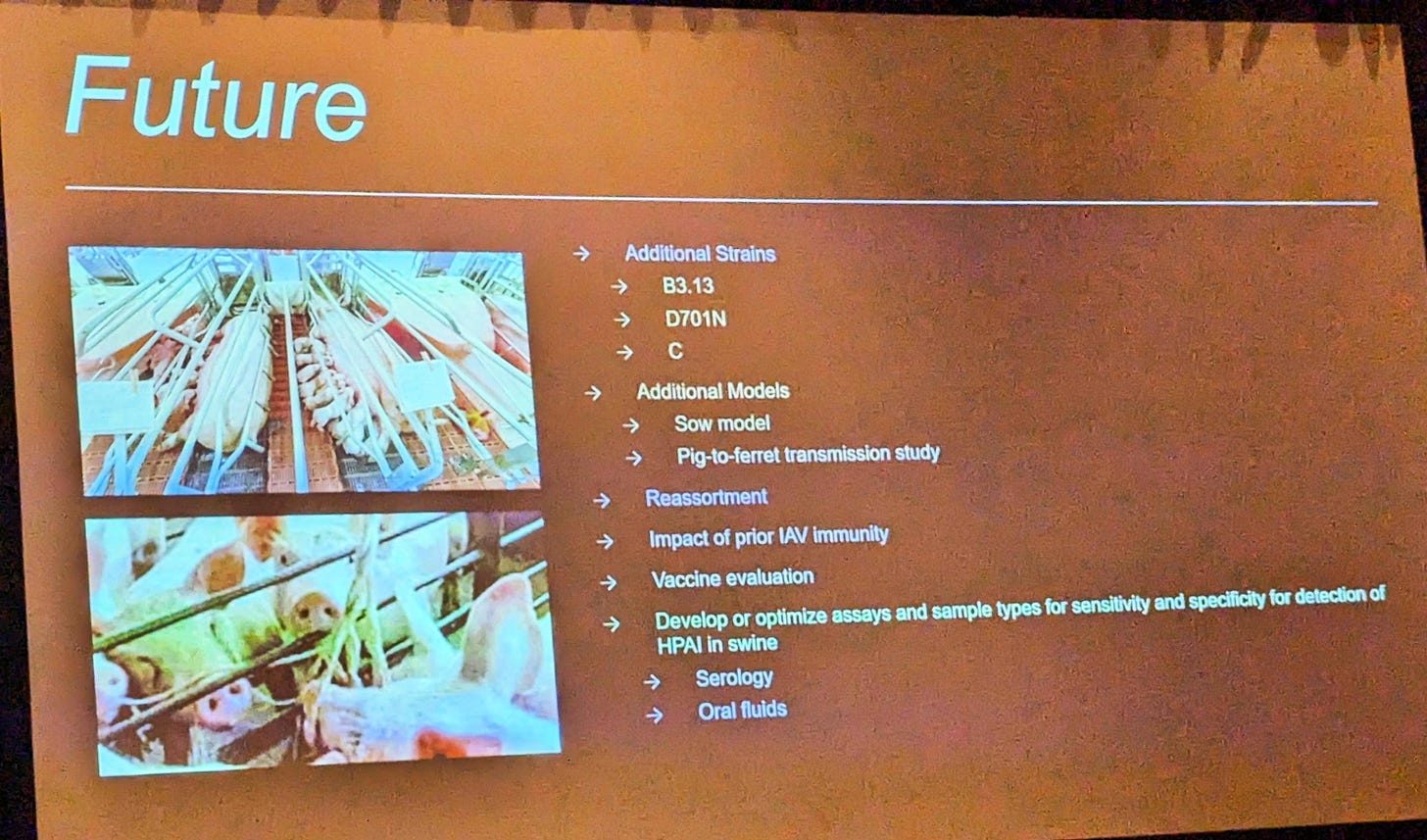

The good news regarding research is that NADC now has several H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 swine experiments planned, starting later in October:

Note that the final bullet point above addresses assay performance (both serology and PCR) in swine samples. That work is a critical near-term objective if surveillance is to be effective. Note also the sow model, which will assess H5N1 viral shedding in sow’s milk and its potential risk for suckling pigs. Potential for reassortment will also be addressed. One interesting question is whether preexisting active or vaccine immunity in swine might provide protection again heterologous infection from H5N1, which is likely a somewhat poorly adapted swine pathogen. Finally, oral fluids will be evaluated as an alternative, but easy to collect sampling alternative for surveillance and detection purposes.

Technical help and increased understanding are on the way, but in the meantime, feral and domestic pigs in California are being presented large doses of H5N1 2.3.4.4b 3.13B generated by the dairy epidemic, both via area spread / fomites and in peri-domestic species such as farm birds, rodents, feral cats, etc. These potential species mortalities as well as their droppings are all fair game for the voracious appetites of omnivorous feral swine and outdoor-housed swine as well.

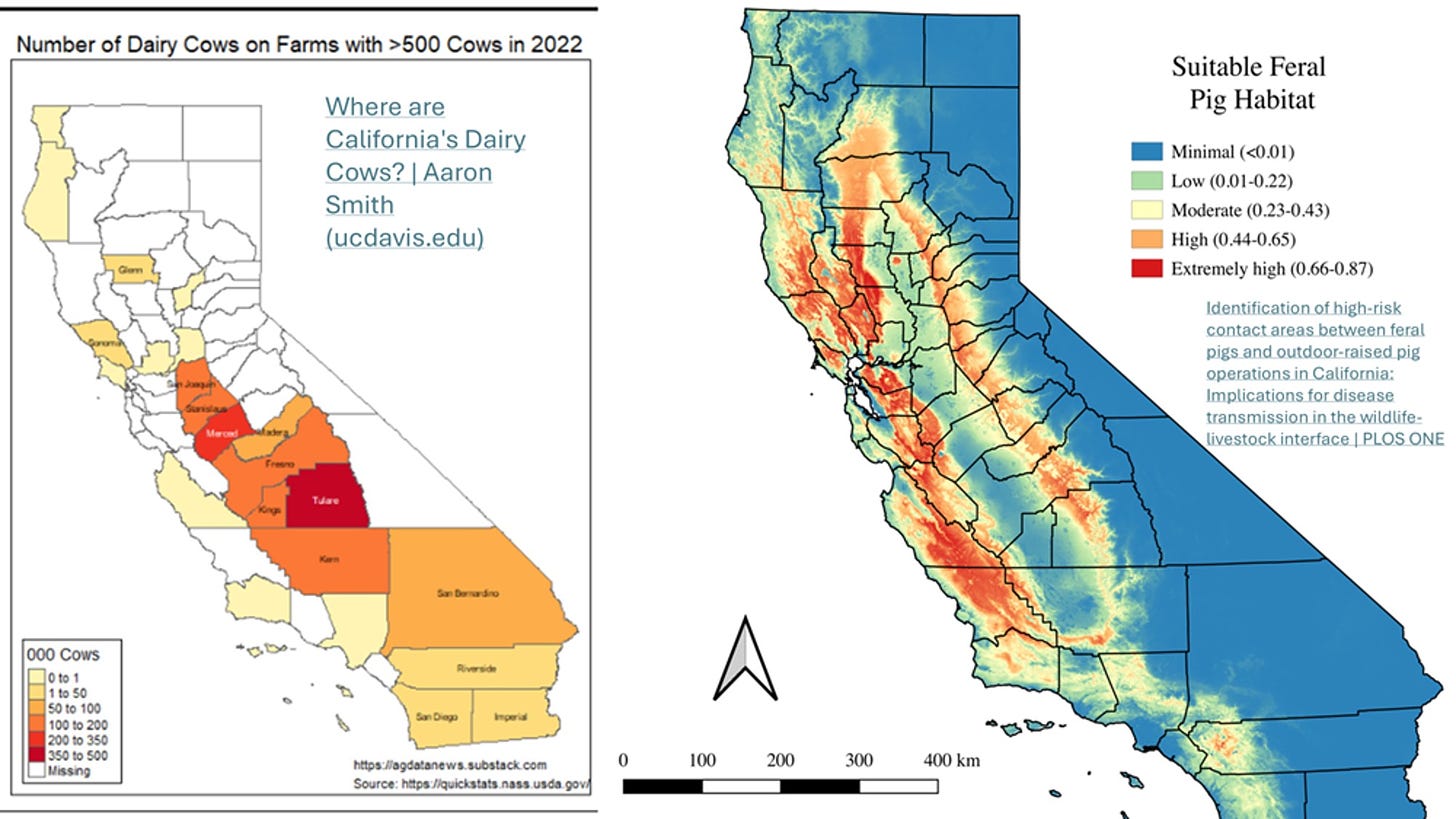

So where are feral pigs in California? Fortunately, a study was completed in 2019 that sheds some light on that question: Identification of high-risk contact areas between feral pigs and outdoor-raised pig operations in California: Implications for disease transmission in the wildlife-livestock interface | PLOS ONE

While designed more to measure interactions between feral and domestic outdoor swine operations, the feral swine maps can be compared with the dairy concentration maps to visualize where feral populations might be most at risk for exposure to virus form dairy herds or peri-domestic species infected by dairy herds:

As the maps show, feral pigs are less concentrated in the Central Valley itself; however, they live in the hills on each side. Any feral pig high risk H5 sampling should be targeted for areas where the infected dairy herds and the feral populations overlap. Local wildlife feral swine experts can undoubtedly identify sites for harvest based on knowledge of infected cattle herds and local feral swine sounder (group) ranges.

For outdoor swine, it’s unlikely that any widespread on farm testing program will be either embraced or successful. Moreover, veterinary individual animal testing infrastructure is already overwhelmed with dairy and poultry testing. Producer education regarding clinical signs for influenza (including possible neurological symptoms for now) should be developed to encourage reporting of cases with compatible clinical signs. However, we have no idea whether pigs infected with H5N1 will present with clinical illness at all or what symptoms they might present versus classical swine influenza case symptoms.

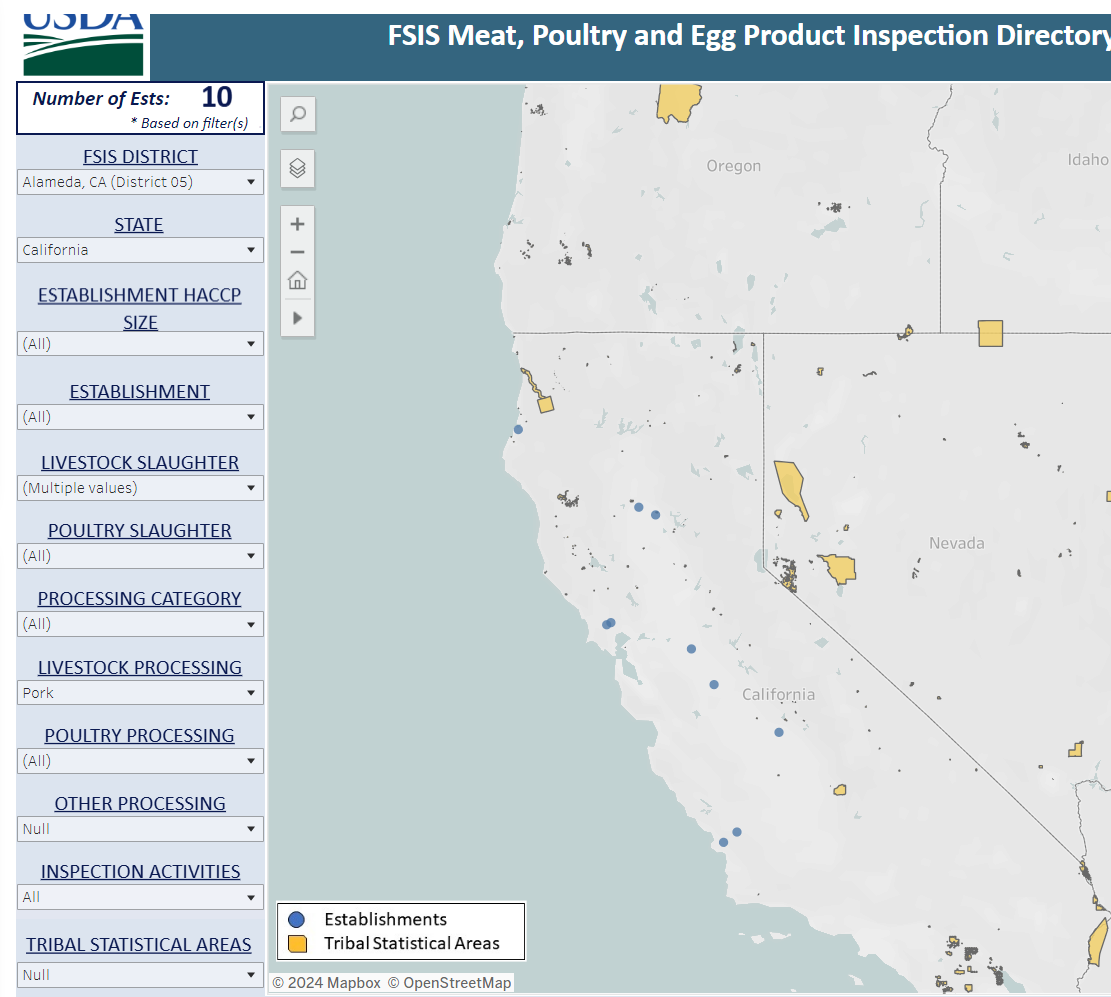

Because of these uncertainties and active surveillance limitations, slaughterhouse testing via oral fluids, pen swabbing, or wastewater sampling at plants for H5 should be considered for market swine. Here is a map of the 10 federally inspected swine slaughter establishments in California with names available on the FSIS website: Meat, Poultry and Egg Product Inspection Directory | Food Safety and Inspection Service (usda.gov):

Some of the larger plants slaughter out of state swine, also, so sampling should be targeted for plants or pens within them handling California-raised pigs, especially from the infected dairy areas. Although H5 sampling in oral fluids and pen swabs are not yet validated, protocols have been proven effective for wastewater, and those processes could be applied/modified for plant-collected samples. Environmental sampling could also be considered at any swine collection points or state-run slaughter facilities if legally feasible.

One possible exception for applying herd testing may be the show pig industry, which is popular with youth in California. These herds undergo a lot of intrastate and interstate movement for sales, shows, and breeding stock movements. If H5N1 is found to infect these pigs, other states may be forced to consider testing requirements for pigs from high-risk areas. A quick search of the 2024 National Swine Registry directory for California showed 16 members, with six of those farms having addresses in the “hot” dairy zones of the state. Show pig producers are not a risk from California alone; Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa, Minnesota, and other positive dairy states also have many show pig producers. Work by Dr. Andrew Bowman of Ohio State University has shown that the “show pig circuit” has been pretty effective in spreading new strains of endemic swine influenza across multiple states. If swine are shown to harbor and possibly transmit H5N1 influenza or its re-assortants, the entire industry has some difficult choices to make regarding ongoing interstate movements for multiple classes of livestock, not just show pigs.

The swine industry, animal health officials, wildlife experts, and one health community have the opportunity and obligation to thoroughly monitor California pigs into the fall and winter while they are under extraordinary viral loads. If pigs in California can be demonstrated to remain free of infection, that data would be invaluable in building confidence that this virus in its current form is unlikely jump to pigs. If the virus is found in pigs, we collectively have the opportunity to develop mitigation strategies within pig populations not so closely tethered to the heart of the national swine industry production base in the Cornbelt, High Plains, and Southeast, where control or elimination of virus once established would be much more problematic.

The dairy industry and regulatory bodies chose to take the less disruptive path with H5N1 in dairy cattle when it hit the TX High Plains area in February-March. We’ll never know for sure, but perhaps spending significant sums of money and effort early to fully attack a KNOWN reportable potentially zoonotic virus in dairy cattle might have been the more prudent and ultimately less costly option.

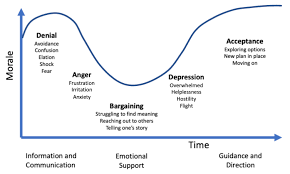

I’ve posted on the grief process graph before - The Grief Process Column (substack.com) The swine industry and regulators have a relatively cheap option here in California to thoroughly look for swine H5N1 infection crossovers in feral and domestic swine under severe infection pressure. Let’s look hard and creatively, then map our best path forward based on what we find. By doing so, we have an opportunity to abbreviate time spent in the first 4 stages - denial, anger, bargaining, and depression. If swine are susceptible, the sooner we reach acceptance so that we can provide guidance and direction, the better for everyone. H5 in California is a real tragedy right now for many and will likely get much worse before it improves. It would be a shame if the swine industry “let this crisis go to waste”.

John