H5N1 Out of the Headlines - Catching Our Breath as We Correct the Past and Assess the Future

Dairy cases slow (Idaho dairy bulk tanks excepted) as wildlife spillover into poultry flocks has eased

I’ve been on the road 3 times in the past 3 weeks, taking in the beauty of Spring on the Eastern Seaboard from northern Georgia to northern Pennsylvania. Two trips were personal; the third occurred last Tuesday to the North Carolina State University HPAI Industry Forum in Durham. The organizers put together a nice 1-day program related to H5N1 risks in multiple species and humans from regulatory, research and industry perspectives. I can’t cover all of the topics fully but want to highlight some of the dairy and poultry information I found particularly interesting.

Poultry is BIG in North Carolina!

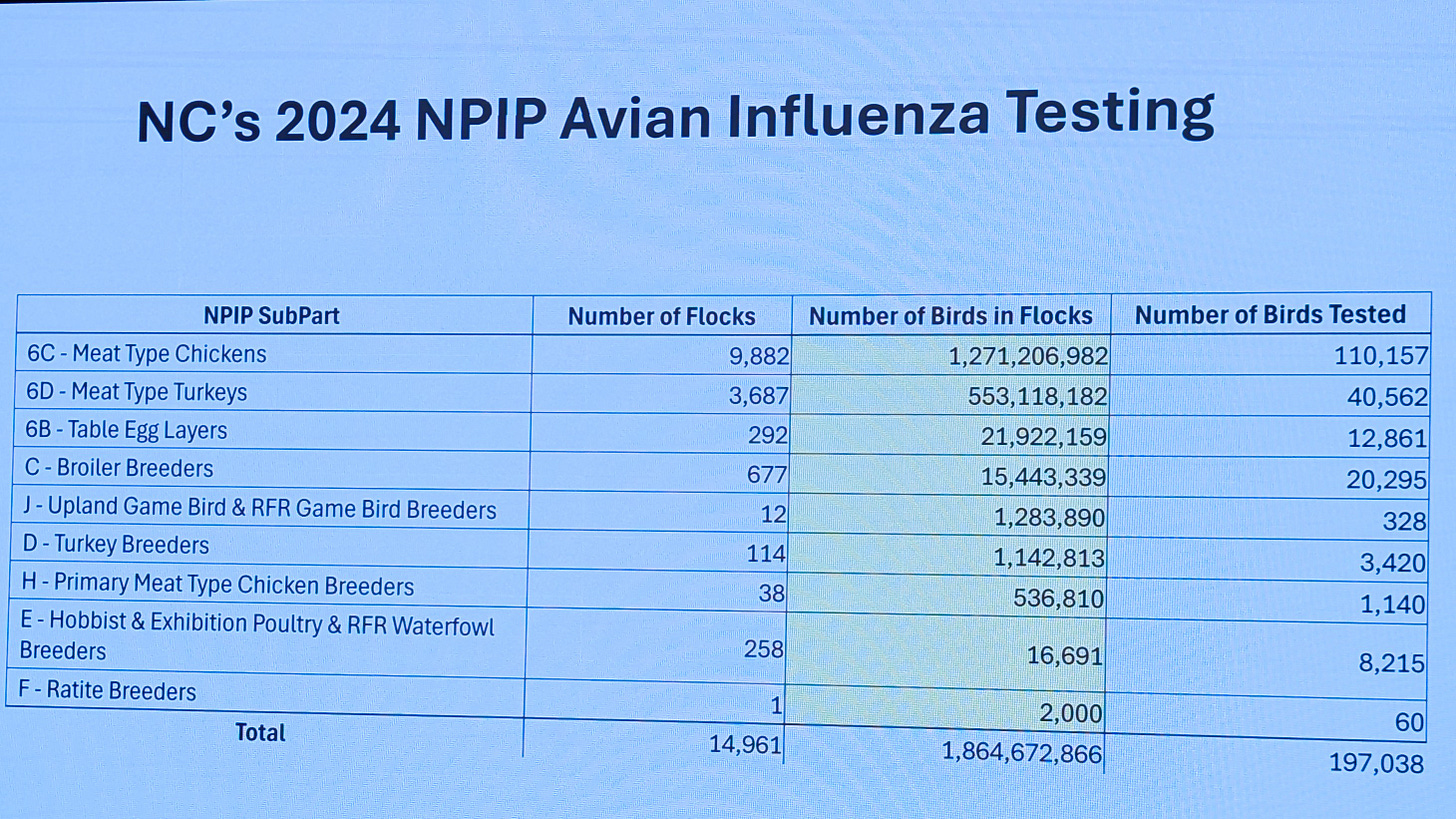

Dr. Rebecca Mansell, Director of Poultry Health, North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Sciences, provided the following showing 2024 poultry inventories and NPIP testing numbers for commercial poultry flocks:

Yes, that is 1.86 BILLION birds produced in North Carolina in 2024. Even more impressive is that the state manages these birds on nearly 15,000 premises, with over 13,000 of these grow-out sites for broilers and turkeys.

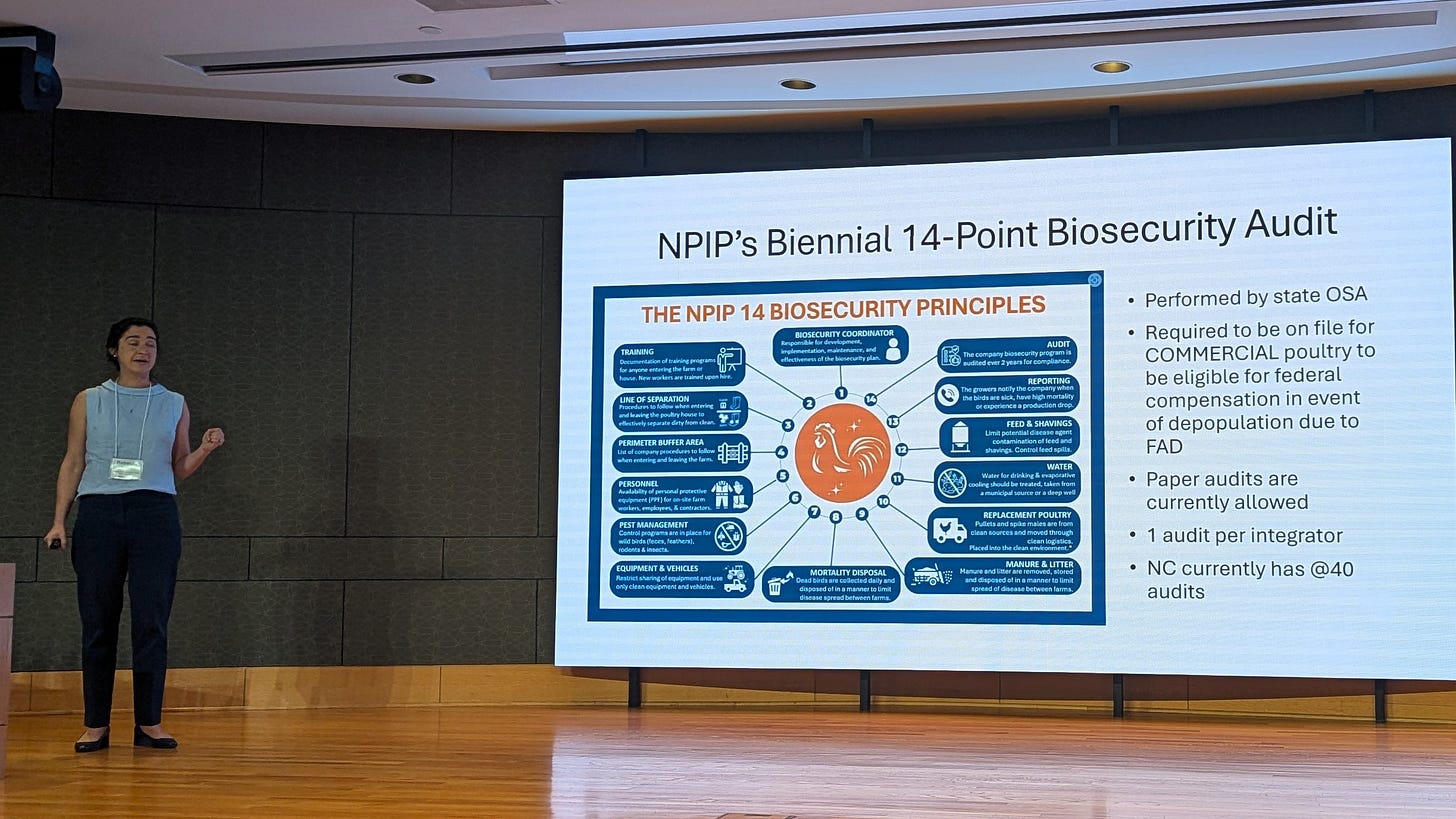

What really caught my imagination in thinking about the sheer volume of the industry was related to Rebecca describing the NPIP 14-Point Biosecurity Audit:

While each audit is specific to an integrator, not reviewed separately for each site, those 14 points must be applied to every one of those nearly 15,000 sites to effectively protect them from infection.

Recall that USDA is now requiring that all producers accepting indemnity payments for depopulated flocks must submit approved audits (i.e. by Rebecca’s staff in NC). It dawned on me that these audit requirements better truly be effective in improving disease protection, because the sheer volume of work required to meet the standards in a state like North Carolina will be substantial; this is not a “token task”.

Hopefully, the efforts at both the producer and regulatory level will pay dividends. It will be important to document failures when breaks occur, in order to further refine exclusion recommendations and/or movement and siting guidelines. The more effort that is put into exclusion, the more important it becomes to accurately determine failure points for future improvements to justify the effort.

One other conversation of interest during poultry discussions related to H1N1-positive poultry meat ending up in raw pet food. Rebecca admitted that the window between the final NPIP influenza PCR test and slaughter was wide enough to allow slaughter of incubating HPAI flocks (0-7 days) prior to development of clinical signs in rare instances. However, moving the final sampling too close to slaughter caused issues with slaughter scheduling for integrators and central lab test turn-around times. USDA VS has piloted a shorter cental lab testing turnaround process in selected turkey flocks in 2 states. An FDA employee in the audience stated that raw pet food companies have been notified that it is their responsibility to develop protocols ensuring that their raw food products are safe and wholesome. Neither FDA nor FSIS guarantees sterility in organoleptically inspected products.

I inquired about the feasibility of developing “Point of Care” (POC) testing protocols to screen flocks within 24 hours of slaughter, with NAHLN lab retesting of POC non-negative flocks. She does not feel that POC testing with “SNAP”-type (ELISA-based) antigen products are sufficiently sensitive and specific for routine use. Perhaps newer lateral flow, PCR or LAMP-based POC products might be feasible to meet speed, sensitivity, and specificity concerns under field conditions so that the industry could minimize the risk for slaughtering H5N1-incubating flocks of turkeys or broilers. In addition to pet food, all participants need to be sensitive to risks for slaughter plant workers, FSIS inspectors, and consumers potentially in contact with H5N1-infected raw carcasses and products. Allowing positive H5N1-infected poultry or meat products through FSIS inspection is not a defensible long-term policy for U.S. agricultural interests in my opinion.

Dairy cattle - Keith Poulsen, the Magstadt Curve, and Jason Lombard

Anyone around H5N1 HPAI topic much in dairy is acquainted with Keith Poulsen, Drew Magstadt, and Jason Lombard, 3 dairy veterinarians “up to their armpits palpating” the H5N1 crossover event.

Dr. Keith Poulsen was on the NC State program and referenced the other 2 veterinarians in his remarks as he summarized what we now think we understand about this disease:

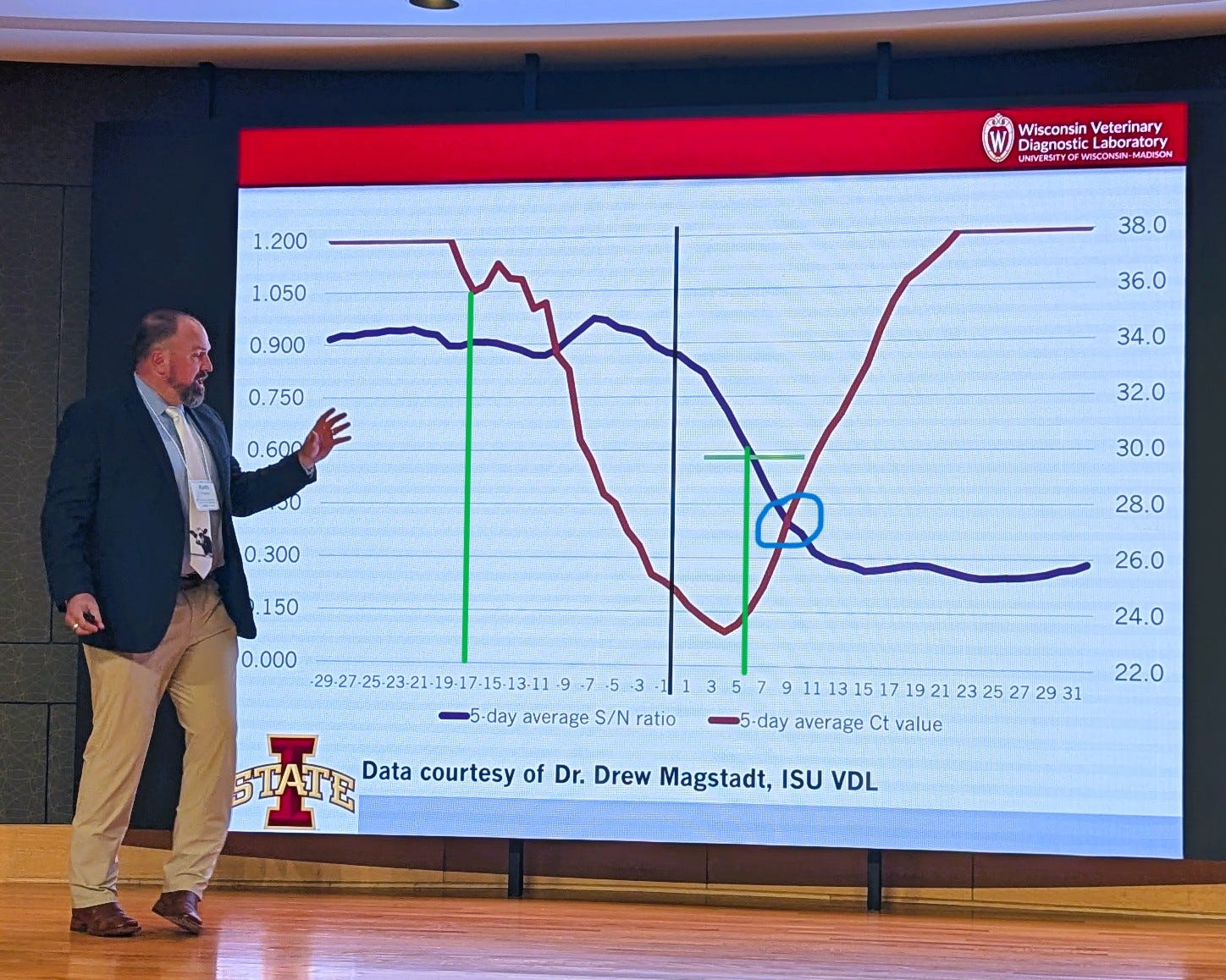

He referenced the “Magstadt Curve(s)”, a compound graph of CT values and ELISA S/N values over time in a series of milk samples fortuitously collected in a “high risk” dairy herd PRIOR to its diagnosed H5N1 infection in the spring of 2024 in data shared by Dr. Drew Magstadt with the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (data shown above). Dr. Magstadt was a co-discoverer of H5N1 in the initially diagnosed case.

The fascinating information in the chart above is the initial drop in the 5-day average milk CT value 17 days prior to initial clinical signs in the herd. Conversely, milk S/N values rose only 5 days post clinical signs, but 20+ days post infection as determined by the CT drop. The inescapable conclusion is that cows are initially infected 2 plus weeks prior to initiation of mastitis and visible clinical illness. This actually aligns with information provided by researchers studying the initially infected Ohio herd as reported by Dimitrov et al and summarized in a column I wrote last summer- (Let's Tackle the Nature H5N1 in Dairy Paper (Dimitrov-Diehl) in More Detail...), where an 11 day+ incubation period was reported prior to onset of clinical disease.

Additionally, Dr. Poulsen called attention to the work of Dr. Jason Lombard, whom I know well from our careers at Veterinary Services, plus since then in conferring on H5N1 in dairy cattle. Keith mentioned Jason’s growing evidence that this virus moves between herds by more influenza-typical between herd spread - exact mechanism(s) still undetermined but likely nasal, oral, possibly dust or insects, etc. with oronasal colonization. I and others have also advocated for this theory, based on epidemiological evidence of explosive spread in areas of high cattle density as well as its onward spread to nearby poultry flocks from infected dairy herds. A good non-referenced summary of Jason’s findings to date can be found here:

Bird flu and dairy cow research | Colorado State University

…One of the early hints that the virus could be spreading through a route other than contact with infected milking machines, Lombard said, was that the virus was spreading through herds quickly, more quickly than would be the case with machine-based spread.

Another clue, he said, came from identifying that antibodies for the virus were first showing up in cattle’s bloodstream prior to detection in the milk. That finding, he said, suggested cattle were being exposed to the virus by a route other than from contact with infected machines…

In addition to learning about how the virus spreads, there have been other initial takeaways from the sampling done by Lombard’s team. Notably, he said, they detected the virus intermittently, which can make the virus more difficult to track because an animal might not test positive one day but might still be shedding the virus. Generally, Lombard said, cattle also appeared to shed the virus for a particularly long period, in some cases more than 10 weeks.

Lombard said the team’s sampling also revealed that cattle could shed the virus up to seven days prior to showing clinical signs — a so-called “subclinical” period similar to how COVID-19 behaves in humans. “By the time you have clinical signs,” Lombard said, “it’s everywhere.” In addition to decreased milk production, the most common clinical signs, he said, have included nasal discharge, decreased feed intake and inflammation of the mammary glands.

Notably, Lombard said, the cattle they tested in Colorado showed a strong antibody response to the virus, suggesting that an avian influenza vaccine could be effective in dairy cattle…

A more detailed paper expanding on these theories, plus much more, was released just yesterday in the Journal of Dairy Science, with Dr. Lombard as the lead author:

J. Lombard1 Jason.Lombard@colostate.edu ∙ C. Stenkamp-Strahm1 ∙ B. McCluskey1 ∙ C. Abdul-Hamid2 ∙ C. Cardona3 ∙ B. Petersen4 ∙ K. Russo5

Take some time to read through this paper, then reflect upon how badly we have botched our scientific inquiry into this relatively straightforward avian-mammalian spillover event. We had the “Magstadt Curve” and the Dimitrov et al Ohio herd case and autopsy data by early summer 2024. We knew this virus was spreading epidemically into poultry flocks as well as between dairy herds in Texas, New Mexico, Michigan, and Idaho. Yet we failed involve local practitioners and to do the basic on-site repeated swabbing and retrospective serological testing required to really understand herd and area infection dynamics.

The animal health establishment (USDA, state, and industry) WANTED to confirm this as a “unique” single-spillover milk-spread lactating cow infection, because it was easier to manage as a primarily “lactating dairy cow only” disease. This approach minimized market and movement constraints on non-lactating dairy animals and beef cattle, which would have been nearly impossible to manage under any meaningful H5N1 testing requirements in today’s animal agriculture infrastructure. So, we kept looking for more evidence to confirm our initial biases, ignoring or not collecting inconvenient evidence to the contrary. Politics and special interests stood in the way of open scientific inquiries as the message, policies, and research priorities were managed from the USDA Secretary’s Office.

I’d argue that H5N1 2.3.4.4b is in fact primarily a mucosal-respiratory-septicemic pathogen with varying levels of clinical illness in most mammals unrelated to lactation status. Lactating cows may exhibit secondary spread to individual quarters with explosive viral replication and shedding in hospitable 2,3 sialic acid receptors in the udder. In this model, the udder infection is actually a secondary sequella (albeit a spectacular one!) in a subset of lactating dairy cattle.

Lactating dairy herds are undoubtedly much more susceptible to higher levels of H5N1 infections than other cattle subgroups, because so much virus is excreted into the lactating herd environment during an acute infection in a naive herd. It will be interesting to confirm to what degree non-lactating cattle on the same farms are susceptible and to what degree neighboring feedlots or cow-calf herds might be susceptible to infection. However, we need to do the testing, not just assure ourselves and others that only lactating dairy cattle are susceptible to infection. We also need to do sufficient prospective bulk tank sampling to find more herds to monitor prior to initiation of clinical illness in high-risk areas- National Milk Testing Strategy may address this if is it finally actually implemented in all states.

We now likely have many historically infected herds from last year’s outbreaks carrying fairly robust immunity against new outbreaks. However, herds turn over and viruses mutate. Idaho is currently reporting 25 new cases in the last 30 days; these are reportedly bulk tank positives with little clinical illness, which would indicate either re-infections with existing virus or new virus infections in recovered herds. State and federal officials will need to monitor for viral changes; the public has not been informed to date of the CT values, genotype (likely B3.13) or degree of nucleotide changes in the new isolates in these herds versus viruses found a year or so ago. We don’t know if these are new viral transmissions to herds or if an existing virus is “hanging out” in subsets of cattle within each herd with reinfection occurring under certain conditions. These are important questions that only VS and/or the Idaho Department of Agriculture can answer given the lack of data transparency to others.

Arizona is another state with 2 new (3 total) H5N1 infections in the past 30 days, both assumed, but not confirmed to be D1.1, as was the first case in Arizona. We have no information on the epidemiology or clinical picture related to either of the 2 recent cases.

We have to assume that workers are being monitored in both Arizona and Idaho; however, immigration enforcement fears are undoubtedly inhibiting worker willingness to allow testing for compatible clinical illness by public health officials. We may not see any reports of human H5N1 cases unless people become so ill that emergency hospitalization is required for survival.

In summary we are at the point where the case load is slowing and released information is slowing even more as federal and state animal and public health staffs are reduced by cuts and less proactive U.S. public health policies come to the forefront. I don’t think our risk for cross species infections or for another human pandemic from H5N1 (or any other agent) has lessened whatsoever; however, our odds for early detection and a timely effective response continue to deteriorate daily.

I talked to an unnamed former VS colleague at the North Carolina meeting, still with a job, but quite pessimistic that VS or the animal health regulatory infrastructure in general has even minimal staff in place to handle a large resurgence in HPAI outbreaks next fall, let alone a major zoonotic pandemic or foreign animal disease response.

I hope industry is ready to step up to fend for itself in the event of a major animal health challenge, including one that involves a One Health threat. The capacity for a sustained federal or state effort will not be there initially. Plan accordingly to protect your interests.

For those of us who still believe, it may be a good time keep up our seasonal influenza vaccines for limited cross protection and to stockpile some N-95’s for those we love!

John