H5N1-Time for the Next Shoe to Drop in D1.1 Livestock Surveillance

Delayed MMWR study on infected household cats finally released; "improved" poultry response plans lack details; added multi-species surveillance needed to properly assess H5N1 viral hot zones

The new administration slowly seems to be addressing H5N1 both at CDC and USDA, with the White House perhaps learning that trotting out the lead administration economist on a Sunday press show with happy talk about increasing the egg supply by killing fewer “unnecessary” flocks may be easier said than done. We still await any substantive plans flowing from that pronouncement by Kevin Hassett a week ago.

Last week CDC released the delayed results of a serological study on bovine veterinarians in an MMWR posting which showed 3 asymptomatic seropositive bovine veterinarians of 150 sampled. This week they followed up with a release of a second delayed H5N1 study: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection of Indoor Domestic Cats Within Dairy Industry Worker Households — Michigan, May 2024 | MMWR

The paper itself does a great job of outlining relevant case histories related to these events, all the data collected from the humans and cats, and the statuses of the farms involved. Shortcomings are evident in voluntary data submissions and timing of collections. I found this timeline at the end of the report extremely helpful in mapping the course of events:

The first take home for me from the case reporting is that the herd associated with Case 1 was obviously infected with undiagnosed H5N1; the farm itself had cat morbidity-mortalities, and the farm worker tied to the cats in household 1 had reported vomiting and diarrhea just prior to cat illness onset. A complete one health investigation of the herd, multiple workers and the household cats at that point would have optimized cattle, feline, and human testing. The farm owner likely was suspicious that his herd might be infected, based on dead cats and infection in the area, but chose not to report it, based on a lack of "clinically ill cattle". Reporting neglect was common at that time, I suspect, because mandatory bulk tank testing was not in place to find sub-clinically infected herds, and dead cat reporting was not required of dairy farms.

That leads to perhaps the biggest practical lesson from the paper- both the farm employees and the farm owners must WANT to find infections if voluntary One Health collaborations are to be effective. In this study (and others) we are consistently testing humans much too late - after cats (or cow herds) have shown clinical signs (day 11 in this study) and workers ceased viral shedding. PCR sampling is a waste of resources and essentially gives “false negative” results at that point in recovered individuals.

If we want to get serious about detecting human H5 infections, we'll need widespread use of rapid test screening in worker's homes or gathering places at first signs of conjunctivitis, fever, or upper respiratory infection (first symptoms), independent of confirmed H5N1 diagnoses on dairy farms, with PCR confirmation, case histories and whole genome sequencing of positive screening tests.

Returning to current news of cats with H5N1 infections, 3 more Portland-area cats test positive for bird flu as infections spread - oregonlive.com:

Three cats from a single Clackamas County household tested positive for bird flu this week, marking the latest infections across Oregon in the past two months, state officials confirmed Tuesday.

Seven cats in the Portland area have now contracted avian influenza since December, including two others in Washington County and two in Multnomah County. At least four of those cats have been euthanized after developing severe symptoms, according to the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

Most of the infected cats contracted bird flu from raw pet food, according to Ryan Scholz, state veterinarian at the state agency. The disease is more common among poultry but can spread to other animals through direct contact with infected birds or by consuming infected raw meat or milk.

A spokesperson for the state agency did not confirm whether the three Clackamas County cats had consumed raw pet food prior to their infections.

Meanwhile another cat was reported to be infected in Clovis New Mexico. The seven cats reported there a year ago were related to B3.13 genotype dairy herd infections; this cat was more likely infected by genotype D1.1 through contact with wildlife.

Finally, Bird flu confirmed in rats for first time, USDA reports. Four black rats were confirmed to have H5N1 avian flu in late January in Riverside County, California, where two recent poultry outbreaks were reported, the agency said. Officials have previously confirmed the virus in mice found on affected farms. The agency's latest update also included other infected mammals in locations around the country, including a harbor seal in Massachusetts, a fox in North Dakota, a bobcat in Washington state and a domestic cat in Oregon.

The list of mammals documented to be susceptible to H5N1 2.3.4.4b continues to expand. The rat detections are particularly concerning, given their widespread distribution and the unknown course of infection in rodents at this time. Persistence in rodent populations could present another ongoing source of potential reinfection for domestic livestock and companion animal populations.

Trump Administration Bird Flu Response Updates

A more recent article from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune captures some of the more recent news related to: Trump administration signals shift in bird flu response

The Trump administration says it has a new plan to fight bird flu, bring egg prices down and stop poultry culling.

Agriculture officials are getting anxious waiting for the details.

“Just this week, the new administration said we may be looking at, you know, not depopulating birds, so we’re trying to understand what that would mean,” Minnesota Secretary of Agriculture Thom Petersen told a state Legislature committee this week.

He wondered aloud if that would mean “we wouldn’t pay the farmers” to cull flocks, as has been the practice.

“This is kind of a day-to-day piece,” Petersen said.

The bird flu outbreak recently entered its fourth year, and Trump officials say the current weapons battling the virus — enhanced security measures on farms and culling all birds at the site of an outbreak — are not working.

On Sunday, Kevin Hassett, director of the National Economic Council, told CBS News’ “Face the Nation” that, rather than culling flocks to prevent the spread of the virus, the Trump administration would have a “better, smarter perimeter.”

National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett said the country needs a better strategy for fighting avian flu than culling birds. (Alex Brandon/The Associated Press)

But the statement — and the promise of a new plan to be released — left some industry officials filling in the blanks.

“We interpret the Trump administration’s comment to suggest they will continue to promote the already utilized control areas in conjunction with additional, newly available tools such as vaccination, to diminish the presence of virus in the environment, thereby reducing the number of birds that are humanely depopulated,” read a statement from Minnesota State Veterinarian Dr. Brian Hoefs.

Last week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture conditionally approved a bird flu vaccine for use in poultry….

As implied by the Minnesota State Veterinarian, it appears that USDA-APHIS is still struggling to interpret what the White House means for its “new policy” for dealing with smarter depopulations. One option that has been discussed privately is “partial depopulation” of multi-barn sites. Outbreaks often initially appear in parts of 1 or 2 of multiple barns on a large site. Theoretically, if infected barns only could be rapidly depopulated humanely before sufficient virus spreads from affected birds to other barns on the site, it might be possible to salvage production in the remaining barns. That could be what Mr. Hassett was deriding as the current policy of killing “perfectly healthy chickens in a perimeter area”, and thus not killing them would be a “smarter depopulation.”

For the counterargument, I’d refer you to last week’s column (Psst- H5N1 DOES Travel in the Air Between Large Livestock Facilities...). Incubating flocks, even in a single barn, emit rapidly increasing quantities of infectious virus very early in the course of infection. Farm managers would need to be extremely attentive in discerning infection early in portions of a single barn or 2, then quickly depopulate that barn to end viral replication quickly on the site. Otherwise, it’s likely that H5N1 virus will have already spread outward to additional barns by the time a diagnosis is made, even if clinical signs are not yet present in them. While initial infections may be due to wild bird contamination as Mr. Hassett states, within site spread occurs partially by aerosol and direct transmission between barns prior to initial diagnosis in additional infected barns.

In practice it’s really difficult to be THAT good with early diagnosis without constant intense production and environmental monitoring of individual barns. Suboptimal partial depopulation is akin to docking a dog’s tail half an inch at a time, with risk for area spread actually magnified by delayed depopulation of a large site that is ultimately fully infected.

Another scenario, as implied by the Minnesota State Veterinarian, is to authorize emergency use of vaccine (or an antiviral?) in some way to prevent transmission to new sites. However, the recent conditional approval of the Zoetis vaccine by APHIS-VS Center for Veterinary Biologics is not yet authorized for sale and use; APHIS must still approve any actual use of this product. Additionally, as a killed product, it likely will require 2 injected doses to provide partial protection. Handling birds twice for partial protection in the face of an imminent outbreak does not add up in my mind to a practical way to protect flocks in a high-risk zone from infection. If or when we have a water or aerosol-administered DIVA (Differentiation of Infected from Vaccinated Animals), single dose, 90+% effective H5N1 vaccine, then its use in the face of an outbreak could prove very successful! But we are a long way from such a tool, given all the researcher pink slips and funding cutbacks brought on by DOGE. There are several additional vaccine candidates in the pipeline for birds, livestock, and humans; however, none are conditionally approved, ready for use tomorrow, or proven to be useful in the face of an outbreak to my knowledge.

The Known H5N1 Situation in North America

I’d like to take a step back to briefly summarize what I think we know right now about the H5N1 2.3.4.4b situation in North America. Our immediate political crisis is in egg supplies and secondarily in pandemic risk; however, we need to understand the entire ecology of the virus across all birds and animals to effectively deal with these crises. No issue can be solved in isolation here - a major One Health principle!

Here in bullet form is what I perceive that we currently understand about H5N1 2.3.4.4b today:

Endemic in wild birds with carriage up and down entire western hemisphere; additionally, seasonal cross-over between the western and eastern hemispheres, leading to an ongoing genomic mixing threat with other world-wide strains.

Known to be infectious to a growing list of mammals and perhaps endemic in an unknown subset of wild and peridomestic mammalian species

Infectious to cattle (and likely other ruminants-goats, sheep), swine, horses, deer (other cervids?), mink

Likely endemic in cattle, but limited testing to date; not documented in production swine, but also not sampled in high-risk areas

2 main genotypes currently:

B3.13 found mainly in dairy cattle - may be decreasing in prominence; has not been shown to be spread by wild birds; spills over easily to poultry and cats; including through raw milk and meat; human infections appear to be less severe (except the Missouri case), with conjunctivitis lesions most prominent

D1.1 - dominant strain in wildlife and mammalian spillover events now; extremely infectious to poultry; documented in multiple dairy cattle spillovers (Nevada, Arizona); domestic livestock adjacent to poultry outbreaks have not been tested; anecdotal reports of infections in beef cattle; human infections also less severe for the most part in poultry depopulation crews; however, the 4 “more severe” human cases reported have been D1.1 - British Columbia, Louisiana, Ohio, Wyoming-Colorado.

Both genotypes appear to spread by contact and aerosol (area) infection, particularly between large herds (flocks) with large volumes of virus emitted and large groups of naive receptor animals. More definitive epidemiological studies are still needed.

Both domestic and larger cats are extremely susceptible (often fatally) to this virus through the oral and respiratory route. Cats may also be capable of passing virus on to other species (humans?).

What is Needed to Complete our Agricultural Assessment

We have several remaining gaps in our knowledge regarding the ecology of this virus in production agriculture. We cannot hope to control poultry infections or detect pandemic H5N1 reassortant threats if we can’t quantify area risks for infection from neighboring dairy, beef, and swine operations in a timely manner. Additionally, we need more rapid and targeted human testing to more accurately assess our workforces’ vulnerabilities.

Here are 5 proposed steps I believe that the new administration should take with state regulatory and industry support:

Widespread multispecies PCR testing in infection-dense areas (OH-IN, PA, CA) - pig groups oral fluids-udder wipes; dairy- herd level bulk tanks; beef nasal swabs - ongoing in control and surveillance zones while poultry flocks are breaking. Question - are livestock herds infected and contributing to spread between infected poultry farms?

Serology in neighboring cattle and swine herds, and horses near recovered dairy and depopulated poultry flocks. Question - has virus spread between officially infected herds and non-tested herds?

Serological studies within recovered dairy herds - lactating, dry cows, heifers. Question - how widespread is infection within diagnosed dairy farms, in addition to lactating sick cows?

(With Consent) - On farm daily influenza rapid-tests for workers - with follow-up PCR on positives. On-farm screening would greatly increase intensity of testing at the time of infection; it would also measure risk of worker spread to animals. Question- are workers contributing to spread or picking up virus from animals??

(With Consent) - Serology in workers post herd recovery Question - to what degree do we have subclinical H5N1 infections in people in contact with previously infected animals?

Taking That Step

I came across this synopsis of the Ohio Pork Producers Annual Meeting H5N1 Information Session Discussion. Kudos to them for broaching the subject in the face of a huge poultry outbreak in the western part of Ohio and east central Indiana. However, I can’t help but ask the obvious question- why no testing?

Here is the likely problem, found within the article itself:

As of now, there is no official recommendation from the USDA or other agencies for how to manage H5N1 if it enters the swine population. While poultry operations immediately depopulate, or rapidly destroy a large group of animals, once an infection is confirmed, dairy farms have treated cows for illness, allowing the animals to recover.

The very nature and uncertainty of the disease and response prevents producers and their veterinarians from doing what critically needs to happen, seek a diagnosis! Perhaps the first thing that USDA needs to accomplish is to sit down with swine and beef producers to hash out protocols for dealing with H5N1 detections in herds. It will be agonizing, but there will be science-based protocols attainable to isolate herds until they can move safely to slaughter or other locations, while monitoring for mutations and reassortants as necessary. The swine industry in particular has long successful experience in highly infectious disease monitoring and elimination protocols (PRRS, PEDV); USDA can learn a lot from them on risk-based strategies for business continuity.

The issue for the red meat industries is that not monitoring and hoping for nothing to happen is not sustainable. We already know both cattle and swine are susceptible to this virus and odds of infection multiply in areas of high viral concentration. USDA cannot continue to leave unmonitored large populations of H5N1-susceptible animals near D1.1-infected poultry flocks as significant biosecurity threats after repopulation.

Vaccines may become part of the solution in cattle and swine operations should surveillance indicate H5N1 infections. Depopulation will almost certainly not be utilized. However, none of these next steps can move forward until we develop baseline understanding of incidence and disease dynamics through surveillance and then develop management protocols through collaborations. I hope I am over-anxious - maybe H5N1 2.3.4.4b is a rare or non-existent issue for swine and cattle herds. However, we won’t know until we look hard through targeted surveillance and report all results from areas most likely to have infections.

It is critical to report negative results for credible results. “No positives” means nothing when no information regarding the number and location of negatives is provided. That is currently the biggest weakness in the National Milk Testing Strategy. “Provisionally Unaffected” states have met some “state-specific” standards; the balance of the states only assure that they are testing to some degree and have not reported affected silos or bulk tanks up to the time the last sample was tested (testing backlog not disclosed). We must remember that a lack of reported positives may not equal negative status for a host of reasons.

This is the main reason why lack of positive results from the NMTS from Ohio and Indiana are of little assurance to me right now regarding dairy herd status in Western Ohio and Eastern Indiana. What dates have silos or bulk tanks been sampled from these high incidence areas? Have the results been returned and reported? Why has milk not been drawn directly from bulk tanks from farms in control and surveillance zones? Have farms been surveyed for any evidence of increased mastitis, pneumonia, dead cats, lactating cows shipped for beef? My concern is that falling back on the NMTS for dairy sector “surveillance” has allowed for slippage in prudent epidemiological investigations of contact dairy herds, given their history of involvement in B3.13 poultry outbreaks in other states.

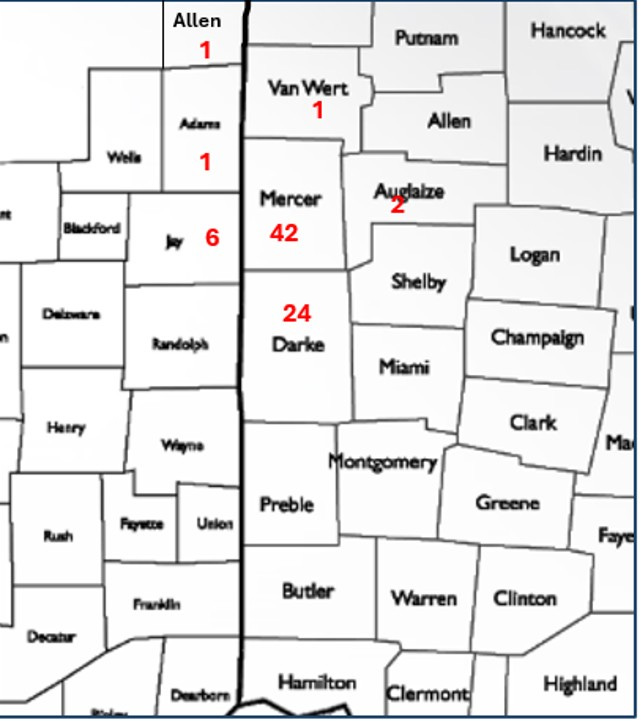

Confirmed H5N1 Affected Indiana and Ohio Poultry Flocks in Adjacent Counties -from 12/27/2024 to 2/21/2025

I don’t relish pointing fingers or poking my nose into state and federal regulatory prerogatives. However, D1.1 is a brand new “dairy issue / cattle-swine issue” that is here now and must be faced. It’s possible that 77 poultry flock infections in 7 adjacent counties in 2 states in 2 months (see above) are all due to wild bird biosecurity breaches and aerosol spread between avian sites only. However, this virus easily infects cattle and swine, which are also found in great abundance mixed with high concentrations of poultry in this animal protein breadbasket.

It’s now time to check these dairy, beef, and swine herds.

John

Thanks for this blog. You have a knack for articulating it all very well

On X, RFK is recommending follow drink raw milk 🤔