Hopeful FMD Follow-up from Germany as of Friday

What about FMD detection in the U.S.? Does CDC's accelerated and decentralized H5 screening initiative show us a better approach for U.S. reportable disease detection?

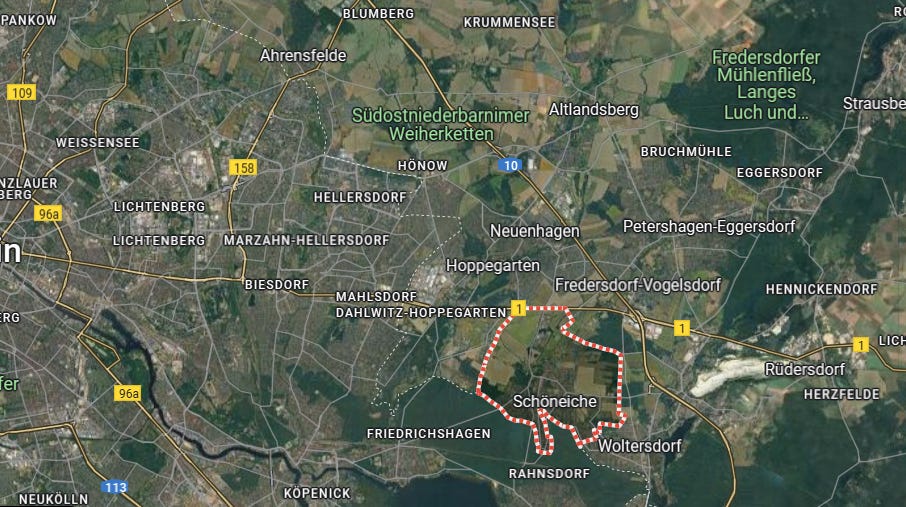

Germany and the EU had a “good week” related to the diagnosed FMD outbreak reported on the outskirts of Berlin a week ago: FLI confirms foot-and-mouth disease in Brandenburg water buffalo | Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute. A Monday report discussed the culling of the index farm and disclosed additional preemptive culling on a farm in a neighboring area: Pre-emptive culling continues as Berlin battles first outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in 35 years | Euronews

On Monday, 55 goats and sheep and three cattle were slaughtered as a precautionary measure on a farm in Schöneiche in Germany’s Brandenburg state days after a foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak was confirmed.

The affected farm had purchased hay from a buffalo farm in Hönow a few days prior, where the disease was first reported and confirmed. A 72-hour ban on transporting cows, pigs, sheep, goats and other animals was immediately put in place to prevent further spread of the disease.

Investigations since have indicated that the disease has not spread further in Brandenburg and is contained within the two farms in Schöneiche and Hönow. “The samples currently being analysed have not shown any further positive results,” says Hanka Mittelstädt, Brandenburg Minister of Agriculture.

“Whether these 72-hours will be extended, or other measures will be taken remains to be seen” she added.

Friday, we received good news that confirmatory testing on a second suspected case exhibiting vesicular lesions had NOT been confirmed as positive:

Second case of foot-and-mouth disease in Germany ruled out

Authorities in Germany have said that a second suspected case of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) has been ruled out following negative test results. The new suspected case had been notified in the district of Barnim on Wednesday (January 15), after animals were found with symptoms that indicated a possible infection with FMD.

Barnim Council confirmed (Friday, January 17) today that the results of the samples taken from the animals were now available. The council said that the findings of both the state laboratory and the National Reference Laboratory (FLI) show that the suspected case has not been confirmed.

District administrator in Barnim Daniel Kurth said that “despite this good news, the situation remains tense”. “Numerous samples that have been taken in the past few days and are still to be taken still need to be evaluated. The situation is also still highly sensitive,” he said. Due to the continued risk posed by the disease in the neighboring district of Markisch Oderland, Kurth advised that extreme caution is still required.

Testing continues, both in the affected area zones in Germany, and in the Netherlands (and perhaps elsewhere?) where many veal calves were shipped from the area in the recent past. Movements have been stopped but will gradually be restored as authorities gain confidence that FMD has been eliminated.

One possible complicating factor is the possibility of infection in feral swine (wild boar) or other wildlife in the area. Ongoing surveillance will be necessary to further assess and mitigate that risk if present. Additionally, the actively infected water buffalo apparently also had serological titers to FMD, indicating a more longstanding infection with longer possible exposure to other contacts. This small herd may have produced milk and/or cheese for consumption and distribution, hopefully all contained and pasteurized. However, farm products are another area undoubtedly under investigation. This whole saga will make for fascinating epidemiological review once assembled; we all hope it’s a short report and not a novel!

U.S. FMD Surveillance and Endemic Swine Senecavirus A (SVA)

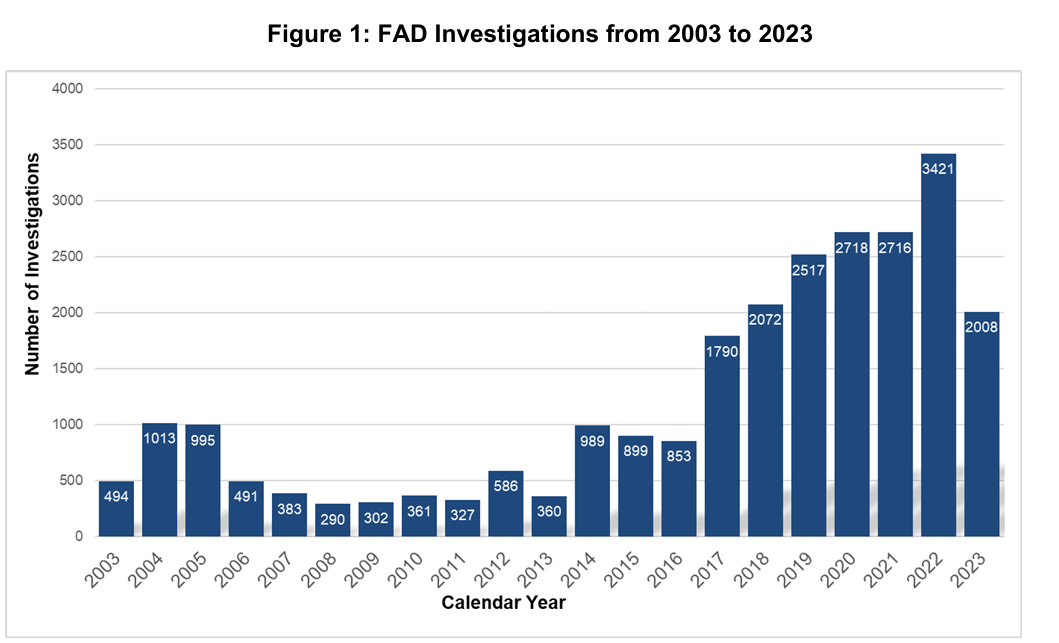

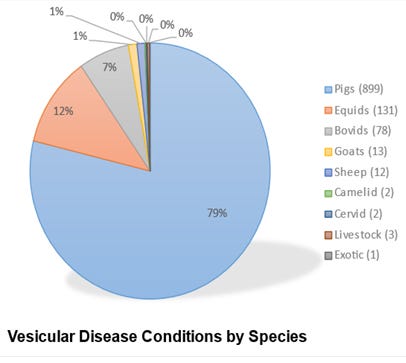

With the German outbreak prominently in the news, I’d like to spend a bit of time reviewing USDA activities related to foreign animal disease surveillance, emphasizing FMD in particular. USDA-APHIS-VS-National Preparedness and Incident Coordination (NPIC) annually produces a report of Foreign Animal Disease Investigations (FADI’s) conducted in the United States. The latest published report covers calendar year 2023, published in March of 2024: CY2023 Update: FAD Investigation Report (link) The entire report is a good read and covers all animal emergency response activities in a variety of species, with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) being a prominent recurring and resource intensive response necessity. A second major detection activity involves officially required investigations of reported vesicular lesions in cloven hoofed animals and horses. First, here is a historical graph showing the total number of U.S. FADI’s from 2003-2023:

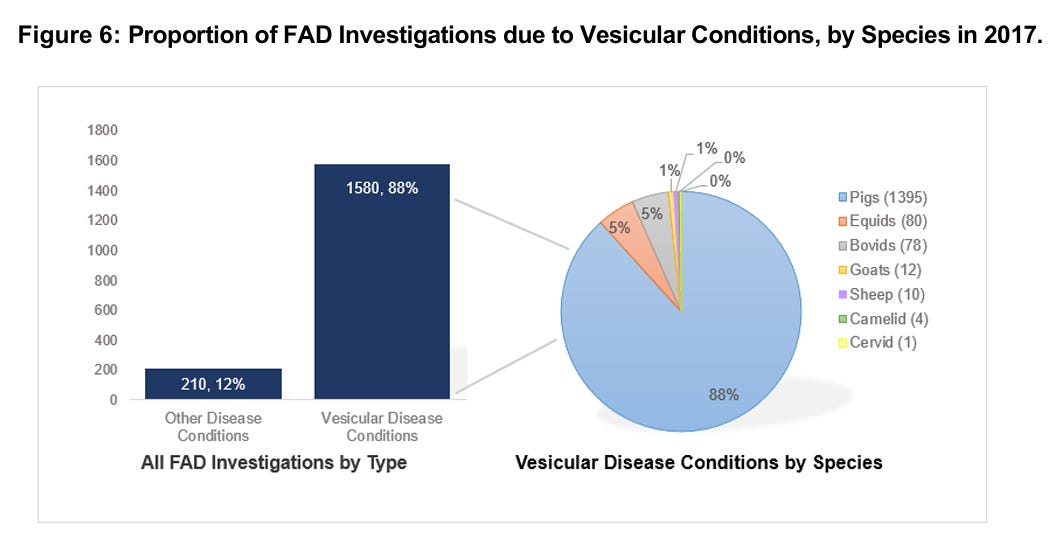

Note the doubling of investigations since 2017, versus 2016 and prior years. Figure 6 from the report provides insight into this trend, explaining the ongoing explosion of vesicular investigations through 2022:

I worked on the swine program staff for VS during that period and spent a lot of time on the issue, because FMD foreign animal disease investigations are both extremely costly and labor intensive in the field and in the NAHLN and the Foreign Animal Diagnostic Disease Lab (FADDL). Despite the costs, no one wants to “ignore” case compatible vesicular lesions in any species. The explosion of Senecavirus A cases quickly became a budgetary and workflow nightmare for both VS and its state and industry partners in several sow and light hog slaughter facilities.

Senecavirus A is a small, non-enveloped picornavirus, discovered incidentally in 2002 as a cell culture contaminant. It is a single species classified in the genus Senecavirus of the family Picornaviridae. This family also contains foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) and swine vesicular disease virus (SVDV). In mid to late 2016, SVA “took off” in the U.S. swine population, causing increasing reports of vesicular lesions, but limited longer term clinical illness or production losses. Its main impact became the difficulties it raised in differentiating lesions in affected pigs from those possibly caused by other vesicular diseases - specifically FMD or swine vesicular disease.

The disease became endemic, particularly in extended time marketing chains utilized for cull sows and light-weight market slaughter plants on the West Coast. Diligent FSIS inspectors at several of these plants inundated VS with swine vesicular lesion reports pre-slaughter. The pigs were picking up the virus from a chronically infected marketing chain environment, incubating infection during a 3 to 14 day holding and transport period, then expressing lesions at ante mortem inspection prior to slaughter.

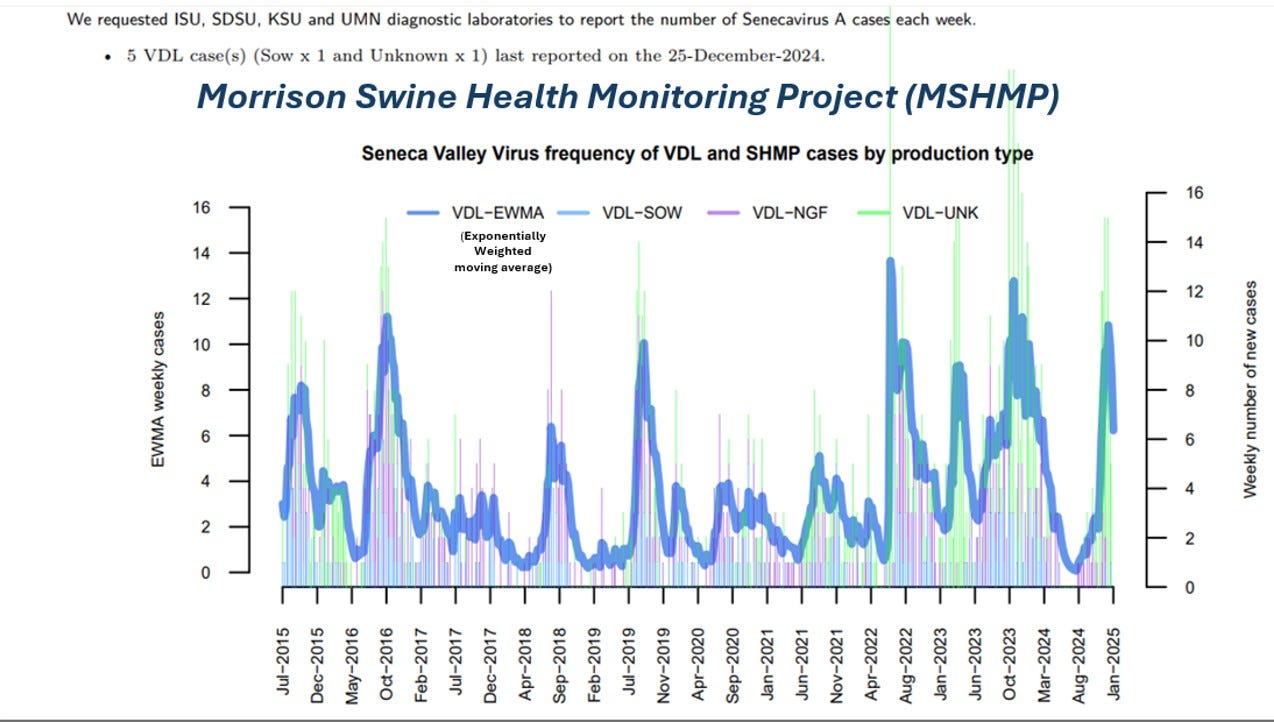

SVA also occurs on the farm sporadically, with varying on-farm FADI reporting compliance. The Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project monitors diagnostic lab SVA case reporting:

Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project. (2025, January 17). Senecavirus A Case Updates (last updated December 24 2024). Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project. https://mshmp.umn.edu/reports#Charts

The virus is obviously endemic in commercial swine farms at low levels with weekly cases diagnosed in the 4 largest swine-centric diagnostic labs. These labs also likely are testing and reporting any FADI market or plant investigation tests here as “unknown cases”. It’s impossible to correlate these D-lab case reports with NPIC vesicular case data due to confidentiality concerns. However, note that the MSHMP data show stable to increasing SVA case data, while NPIC data shows greatly decreased cases in 2023, down to 899 swine cases. It’s possible that the marketing chains have cleaned up and improved biosecurity; however, it is more likely due to reporting fatigue or a forced shifting in federal and state regulatory priorities induced by the H5N1 outbreak in poultry.

There is another issue worth considering in the 2023 NPIC report. Yes, the total number of swine vesicular cases dropped to 899; however, VS and its cooperators conducted a total of only 240 other species investigations.

We have 87 million cattle on inventory in the U.S. and tested 78 cases -we annually test less than 1 in a million bovine animals in the U.S.! We likely missed FADI’s on many pigs with vesicular lesions; however, we likely missed even more cattle, sheep, and goats with “compatible” vesicular lesions. While endemic SVA has made reporting in swine more problematic, it only highlights the unpopularity and unworkability of the current FADI process for the entire livestock production and processing industry.

We currently require reporting of visual lesions followed by official investigations, stop movements, and centralized confirmed negative tests to allow resumption of business continuity. I’ve heard horror stories of movements held up for 7 days plus awaiting communication of confirmed central lab negative test results. Those producers (and their acquaintances) won’t give the system a second chance when lesions reappear.

In reality we would swamp our NAHLN and NVSL labs if EVERY compatible vesicular and hemorrhagic illness in swine, cattle, and sheep were reported on any day on the U.S. We cannot write clinically based case definitions that adequately screen individuals for cost-effective FAD screening. Furthermore, we don’t have individuals in place across our animal populations to consistently observe them. Our lab-centric rationales are antiquated and driven by insistence on single-animal testing.

However, centralized diagnostic systems for high consequence diseases based on reported clinical signs are in place world-wide as standard operating procedure across OIE. It has worked equally well for rapid detection of:

FMD in Germany last week, as it did for

ASF in the Dominican Republic in 2021, as it did for

ASF in China in 2018, as it did for

ASF in Georgia in 2007, as it did for

FMD in the UK in 2001, as it did for

CSF in the Netherlands in the late 90’s

…in other words, not rapidly at all! (Yes, it works for HPAI, mainly because many birds die in 48 hours regardless, and extensive surveillance systems have been developed to minimize outbreak-to-depopulation times - poultry companies don’t wait for lab confirmation to make decisions in the U.S.).

Until recently, centralized official diagnostics was the only option due to costs and expertise required. With the advent of molecular diagnostics, the U.S. made a half step to move volume testing closer to the field with the NAHLN structure for earlier presumptive diagnosis and outbreak capacity building at state-based labs. However, final confirmatory testing for initial diagnoses remains at the national lab(s). Physical transfer of samples collected by approved regulatory officials is still required. The total investigation time frame remains extended.

CDC and FDA this week announced some policy changes to accelerate official testing for H5N1 in humans: Health Alert Network (HAN) - 00520 | Accelerated Subtyping of Influenza A in Hospitalized Patients

…Enhancing and expediting influenza A virus subtyping of specimens from hospitalized patients, especially from those in an ICU, can help avoid potential delays in identifying human infections with avian influenza A(H5) viruses. Such delays are more likely while seasonal influenza activity is high, as it is now, due to high patient volumes and general burden on healthcare facilities. Additional testing also ensures optimal patient care along with timely infection control. Furthermore, expediting transportation of such specimens to commercial or public health laboratories for additional testing may also accelerate public health investigation of severe A(H5) cases and sharing of information about these viruses…

One of the major lessons taken from the COVID19 outbreak was the abysmal lack of approved diagnostic speed and capacity in early 2020 during the pandemic’s logarithmic growth phase. CDC and FDA were unable to disentangle themselves from their own rigid policies to unleash vital field-testing capacity needed to assess the broadening scope of the outbreak. CDC insisted upon retaining total control and centralized testing via exclusive utilization of a flawed COVID test in early 2020, despite the obvious need for much greater and improved molecular testing capacity. It appears that with this HAN, CDC and FDA have taken that lesson to heart - get the damned testing done- in volume and without delay!

As we near 1000 positive H5N1 dairy herds and hundreds of poultry flocks, we are still making presumptive diagnoses on every case at NAHLN laboratories only and shipping EVERY case to NVSL at Ames for confirmatory testing and sequencing. Now we are slowly further expanding the testing to milk silos and bulk tanks in some cases. When can we stop requiring the samples themselves in Ames and start requiring results and sequences from NAHLN’s and other facilities proven to meet necessary assay standards?

Perhaps more to the point, when can we entertain field-based Point of Care and environmental sampling (FMD bulk tank screening has long been validated!) as efficient early detection tools to supplement ineffective FADI’s? Early detection is a whole separate set of discussions and likely quite agent-specific; however, until we are willing to at least entertain the idea of distributed screening and testing for agents of concern, we are doomed to getting the same results we always gotten (newly diagnosed FMD seropositive water buffalo and H5 positive sewage with undiagnosed sick dairy cows).

John