Human H5N1 Case(s?) Information from Missouri Continues to Unfold Late Friday

Case study on how NOT to release information from the local level through CDC to the public

This past week has been one for the record books for CDC’s public affairs staff! Significant details finally came to light on Friday afternoon after a week of repeated assurances that this was a “one-off” case of unknown origin and no evidence of human transmission. Here is the official CDC press release from late Friday afternoon:

CDC A(H5N1) Bird Flu Response Update September 13, 2024 | Bird Flu | CDC

Missouri Case Update

Missouri continues to lead the investigation into the H5 case reported last week with technical assistance from CDC in Atlanta. The case was in a person who was hospitalized as a result of significant underlying medical conditions. They presented with chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and weakness. The person was not severely ill, nor were they in the intensive care unit. They were treated with influenza antiviral medications, subsequently discharged, and have since recovered. One household contact of the patient became ill with similar symptoms on the same day as the case, was not tested, and has since recovered. The simultaneous development of symptoms does not support person-to-person spread but suggests a common exposure. Also shared by Missouri, subsequently, a second close contact of the case – a health care worker – developed mild symptoms and tested negative for flu. A 10-day follow-up period has since passed, and no additional cases have been found. There is no epidemiologic evidence to support person-to-person transmission of H5 at this time. CDC's original report about the case in Missouri is available: CDC Confirms Human H5 Bird Flu Case in Missouri | CDC Newsroom.

CDC has attempted to sequence the full genome of the virus from the most recent case of H5 reported by Missouri. Because of low amounts of genetic material (viral RNA) in the clinical specimen, sequencing produced limited data for analyses. Full-length gene sequences were obtained for the matrix gene (M) and non-structural (NS) genes and partial gene sequences were obtained for the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes. The available gene sequences are all closely related to U.S. dairy cow viruses, and similar sequences have been found in birds and other animals around dairy farms, raw milk, and poultry.

The HA gene sequence confirms that the virus is clade 2.3.4.4b, and the NA sequence was confirmed as N1. There are two amino acid differences in the HA that have not been seen in sequences from previous human cases. These amino acid differences are not known to be associated with changes to the virus's ability to infect and spread among people. However, both differences are in locations that may impact the cross-reactivity of clade 2.3.4.4b candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs). Additional antigenic testing is planned. One of the two amino acid differences (HA A156T) has been identified in fewer than 1 percent of viruses detected in dairy cows. The other amino acid difference (HA P136S) has been seen in only a single dairy cow sequence.

The admission on Friday of clinical signs in a close patient contact as well as symptoms disclosed (with a negative influenza test) in a health caretaker brought predictable concern from reporters and experts commenting on the latest information in early news reports after the latest press release:

NY_Times-2024/09/13-bird-flu-missouri

NBC_News.com-cdc-says-no-clear-source-bird-flu-infection-missouri-patient

To summarize, 2 Missouri residents become ill around August 22nd, one with preexisting conditions that led to hospitalization. Diagnostics included a positive influenza matrix test on the patient, negative for H1-H3, then diverted for novel influenza testing. It was confirmed to be H5 positive by CDC. At some point after patient diagnosis, a close contact living in the same household reported illness to officials. It’s unclear when either local and/or CDC officials may have known that the close contact had also been simultaneously clinically ill with the patient; however, the contact was not tested via PCR since clinical recovery made success unlikely. State officials also disclosed that a health care professional reported illness during the treatment period for the patient; however, influenza A testing was negative for the provider. At this point, none of the previously ill subjects have been tested serologically for H5 antibodies; however, discussions to accomplish that are continuing. Efforts also continue locally to monitor for any evidence of increased signs of human ILI in the local population, and potential food and/or animal sources of infection for the patient(s) continue to be reviewed.

Alexander Tin is a reporter for CBS News covering health issues and HHS-CDC-FDA and USDA press conferences. I received his permission to link to his notes for better insight into comments made at agency press conferences related to high profile events. September 2024 | Alexander Tin’s notes (tinalexander.github.io)

On Thursday, Nirav Shah, CDC [00:30:21] stated the following:

We’ve not seen any evidence of person to person transmission. None of this individual’s close contacts have any evidence of onward transmission. None of the individuals that this individual came into contact with have developed any signs and symptoms. So we haven’t seen any evidence of it at this time.

It seems incomprehensible to me that a CDC spokesman would knowingly lie 1 day before the agency changes its story. I think it’s much more likely that communications between the patient and contacts and local, state, and federal officials have been less than forthcoming. Someone along the chain “came clean” late in the week. Rather than throwing stones, it’s best to thank all parties for correcting the record at this point, so that everyone can move on with next steps. People sometimes need time to understand the gravity of an investigation and why seemingly private information needs to be confidentially shared to answer important questions.

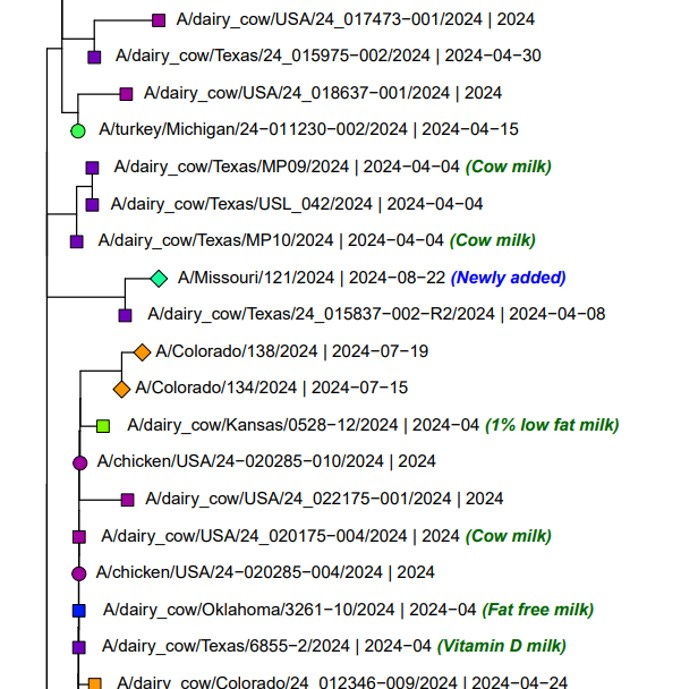

CDC had relatively good news on the sequencing front, gathering sufficient coverage to determine partial H5 and N1 coverage to allow GISAID deposition of those partial sequences. Here are screen shots of where they fall in the phylogenetic trees:

H5 Gene Graphics Output (gisaid.org)

N1 Gene Graphics Output (gisaid.org)

As stated, both segments fall squarely in the dairy clade isolates from the current outbreak. The H5 in particular is closely related to an April 8th Texas dairy cow isolate.

Finding an animal source for this outbreak is a big challenge, with no obvious epidemiological links. However, I’d suggest starting with dairy cows, given the close phylogenetic relationships. Even if a wild animal, cat, or bird ultimately spread the virus to the household, it likely was brought into the area by dairy animals. That seems to have been the case in a large percentage of the wild animal isolates in the USDA mammalian list: HPAI Detections in Mammals (usda.gov) While a host of peri-domestic and wild animals have picked up the Eurasian-American H5 lineage strain since early 2024, almost all of them have been isolated in areas with dairy herd or poultry outbreaks. This clade has not been widely isolated outside of areas already “seeded down” by domestic animal infections. That may partly be a sampling effect, since wildlife is usually sampled in areas surrounding outbreaks.

As a start, here is a map of the January 1, 2023, dairy population in Missouri, as shown in the map below in the upper left corner of the illustration:

A large share of the cows inhabit the southwest quadrant of the state. We don’t know where the patient is located in the state; however, given the clade of the virus, it MAY be reasonable to assume he/she resides in that area, or could be affected by wildlife from that area. While Missouri has reported no clinical H5 cases in dairy herds, that does not mean that the state is free of infection.

Harrison, Arkansas, just south of the border, is a point for regular H5 sampling in the WastewaterSCAN monitoring program. It flashed positive twice for H5 in July and August (shown above). In fact, the August reading at 537.2 copies/gm is the highest reading I could find in the dataset. Doing a quick Google search, Harrison is also a distribution point for Hiland Dairy, which processes milk for Dairy Farmers of America (DFA), a large dairy cooperative serving Missouri, among other states. The distribution point likely disposes of some waste, spillage, or expired product in distribution, allowing milk residue to flow into the wastewater system. Since Harrison is a relatively small sewer shed, the distribution plant runoff likely has a relatively large impact on assay concentrations.

It is thus very plausible that sampling and sequencing wastewater in Harrison Arkansas could provide a good “pooled” sample for the Missouri dairy herd without requiring permission from producers and their processing cooperative for testing milk samples for H5. I hope that the samples from July 15th and August 19th are still available for sequencing; the results would be of great interest given the human isolate!

Even if the wastewater sequences should closely match the human case, that still does not provide a link to the patient. It could imply but not legally prove that the virus is in a dairy herd or herds in the catchment area of the processing plants feeding the distribution point in Harrison; however, any tracing upstream would be up to DFA and state animal health officials. Wildlife and peri-domestic sampling would fall to state and federal wildlife agencies. Regardless, matching wastewater results get the virus source one step closer to the patient, allowing greater localization and targeting of future surveillance efforts.

For those squeamish with naming commercial entities or parts of states in the dairy business, I’d point out that everything I’ve posted in the last few paragraphs are available on public web sites, both private and governmental. Google Maps labels companies and includes photographs of facilities, including farm production sites. Expectations for anonymity are past, given concentration in the industry and the sophistication of information collection in the public sphere now freely available on-line.

Even with all the developments last week, the immediate risk to H5N1 still remains classified as LOW by CDC and world health experts. It lacks several known mutations required for efficient human transmission. Human to human transmission has yet to be documented, yet alone sustained. The documented cases have remained relatively mild, even in people with preexisting conditions.

Countering that, we now have a case without known animal exposure. A second case in the same household is possible, either with the same route of exposure or from human-to-human transmission. Serology may help sort that out, as well as provide more confirmation that a third contact with clinical signs was indeed not infected with H5N1.

I have not dealt with the animal side today, other than implying that there could be H5N1 in dairy herd(s) in Missouri. It bothers me when representatives in the animal health industry so quickly point out that sources could be birds, wildlife, cats, etc., (which is obviously true), but minimize dairy cattle as a possible source of a virus that the industry has been very slow to admit, and slower to actually test.

About 11 years ago I was working at Veterinary Services with swine influenza at county and state fairs occasionally spilling over into exhibitors. At the time many in and associated with the industry were still in denial of the problem, fresh off the pdmH1N109 trauma. A long-retired animal health official swore up and down that we could never just blame the pigs and should not test them- it could be mice or birds, or??, despite CDC sequencing the isolate as a 100% swine virus in the human patient. The swine industry has now come to the point that swine show veterinarians may diagnose subclinical influenza in fair pigs and warn exhibitors to watch closely for signs of ILI in both the pigs and in themselves. I’ll predict that we’ll be there someday with H5N1 - proactively monitoring for infection blips and providing information to public health, rather than waiting for disasters. THAT will be One Health in action!

John