New California, New Mexico, and Michigan Cases, CO Bulk Tank Progress Analysis, and a Lab Mask Fomite Study??

A Bit of Everything on a Long Weekend Break

New Cases:

The dairy H5N1 lull was short-lived as Michigan reported a new herd on Monday, a New Mexico case was listed on Friday (their 9th case, but their first case since April 17th!), and then the number one dairy producing state, California, reported that 3 herds in the Central Valley had been confirmed as infected Friday evening.

I’m uncertain that dates of first cases or intervals between reported cases really are of great meaning, given the ongoing dairy industry resistance to reporting cases. Some of the wildest stories making the rounds regarding physical threats made to those reporting cases or made to workers with URI symptoms are both criminal and frightening if true. This behavior is all the more mysterious to me given that no one has lost access to markets from reporting infections to my knowledge. Unwholesome milk from affected cows is only withheld from market until it returns to normal parameters. Quarantines only apply to lactating cows testing positive prior to movement. We owe a debt of gratitude to those producers who have stepped forward to do the right thing and to those veterinarians who have maintained standards despite losing clients in this fiasco.

Whatever the reporting shortcomings, each of the new states reports last week offer some food for thought. First, in Michigan, cases continue to be reported at the rate of about one per month. County designations would suggest these are likely new cases, not reinfections, since the last 2 are both in a new county. Michigan has reported a total of 36 cases, with 28 still listed on the Michigan H5N1 web site as active cases.

Michigan has led the nation in proactively looking for new H5N1 cases in dairy which indicates that infection has drastically quieted down there. Conversely, only 8 sites have returned to negative status if the web site is current. Early in the outbreak the Michigan State College of Veterinary Medicine planned to engage with interested producers in extended epidemiological investigations of affected herds to track herd progression and resolution over time. I look forward to any information MSU can share regarding their findings.

New Mexico has not issued any information regarding their latest case, which USDA disclosed on Friday. However, the 4.5-month lag since its last case implies this to be unrelated to any earlier reported New Mexico cases. Without bulk tank testing and a history of cattle movements (information hopefully available to local investigators) it’s impossible to draw any firm conclusions regarding the origin of this case.

The same situation applies to the three California cases confirmed by NVSL on Friday evening. These are the first reported cases in California; however, repeated positive H5 and matrix gene wastewater sampling across California has led to suspicions the virus may have been in the dairies unreported. Here is a map of the dairy farm locations in the state of California:

More facts may or may not come to light from the epidemiological work done with the 3 cases, depending on the degree of cooperation the individual producers and the industry as a whole choose to provide to investigators. We’ll soon have a better handle on the amount and quality of information regarding H5N1 in dairy to be shared with the public by California dairy producers.

As with Colorado and Texas-New Mexico, the dairy industry is also intermixed with significant large poultry firms:

Finally, the Pacific wild bird migration flyway courses directly over the valley, adding one more complicating ingredient to the mix:

There is a reason everyone has been so nervous about California’s status; it’s the number 1 production state with 20% of the nation’s milk production and it sits in an ecological landmine for both poultry and wildlife.

To channel my late, very wise, and beloved dad: “We’ll wait and see…”

Colorado Bulk Milk Review-Analysis:

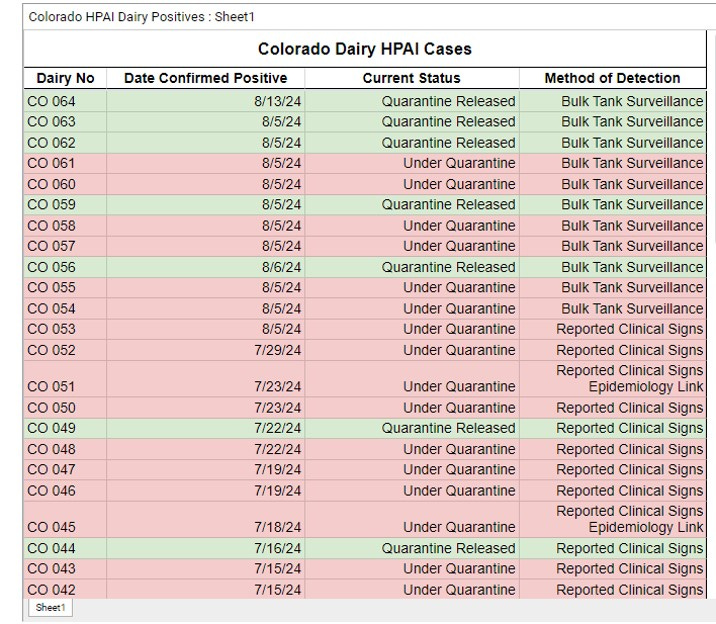

Some things have been happening right under our noses on the Colorado H5N1 Dairy Case website. Here is a screen shot of the most recent case list with the last new case #64 listed on 8/13/24:

Note that 7 of 14 bulk tank surveillance quarantines issued since August 6th, including the last (64th) case, have already been lifted. 2 bulk tank surveillance cases are found deep down on the list as CO03 and CO04 (see below), herds which broke early with infection, then I assume were released from quarantine, only to test positive again when mandatory bulk testing came into play:

Those 2 herds apparently returned to negative bulk tank tests again, since they now are listed again as “quarantine released”. These rapidly cleared results provide hope that the virus does indeed clear herds at detectable levels in bulk tank sampling, at least for a period of time.

Less encouraging are herds 6 and 12, which appear to remain under quarantine 2 1/2 months after diagnosis. Every herd’s cattle flow and risk structure is different, so a lot more study is needed by epidemiologists and dairy herd health specialists at the farm level to understand why many farms go negative, but some do not.

It would also be interesting to know what percentage of the bulk tank positive herds that subsequently returned to negative status never showed cases of full-blown clinical mastitis in cows in lactation. We have anecdotal reports of bulk tank samples going positive 2 weeks prior to clinical mastitis, suggesting a “preclinical” systemic infection of the cow with viral shed in the milk. Can that stage occur in herds without proceeding on to clinical mastitis, which is the case-defined disease?

These questions are another reason why weekly bulk testing paired with ongoing herd evaluations and paired serology studies in herds from the time of first bulk tank positivity to the end of clinical illness are so critical:

How many cows are getting sick

How does the virus appear to be spreading

Do non-clinically infected cows shed virus in milk or via other routes (oral, nasal, urine, semen)

When do antibodies appear and in what percentage of the herd

If the entire herd does not seroconvert, is there evidence that the virus may “bounce around” at low levels in uninfected cows, maintaining herd infection

In cases of reinfection, do previously infected cows have protection, i.e. is infection limited to new additions or previously uninfected cows

Swine sow herds face a very similar situation when new PRRS virus strains infect a site. With years of experience, pooled sample protocols have been developed to monitor declining herd infection status to estimate when the herd may be returning to negative status, as shown in this paper:

The dairy industry has to learn the basics regarding H5 infections before it can begin to employ such strategies to assess herd H5 status; however bulk milk samples are the perfect pooled samples for testing! The biggest question may be the odds for hidden infections in recovered herds or reinfections from sources that can’t be controlled through biosecurity. Those have been challenges enough for the pork industry; however, the cost of PRRS is so large that people continue to strive towards ways to eliminate it by measuring herd elimination progress.

Applying a Human Mask Lab Study to Cows?

I read the following post by my favorite source, Michael Coston, late last week:

I readily admit my bias against mechanical movement of respiratory viruses as a major source or spread between sites or to new victims. I’ve always had trouble with the concept that enough virus could be picked up, survive on or in some fomite, then be deposited onto a respiratory mucosal surface in sufficient quantities in a viable state to induce infection. (Note: something like ASF or CSF or even PRRS is completely different, where it can be cooled or frozen, then ingested to hit the tonsils.) But influenza and coronaviradae it seems to me really need to be “in the air” or at least “on the dust or water droplets” to hit the receptors for transmission.

This paper along with the papers it cites add some credibility to those thoughts. It’s tough to carry enough virus on fingers, even from very dirty masks, to infect anything. Bringing it back to dairy H5N1, the question I keeping asking is: “What is the mechanism by which sufficient viable virus can be transmitted by any fomite:

to a new farm,

to the milking facility

to the milking line

to the wash solution

to the milking claw

up the inflation against the natural milk flow

through the teat sphincter

up the milk quarter’s sinus lined with epithelium lacking 2,3 receptors

and finally into the secretory alveoli, where the proper 2,3 receptors await?

We haven’t even shown transmission of sufficient viral loads by fomites to new farms with real world survival times at infectious doses (Step 1). Once we get on the farms all sorts of even rudimentary biosecurity barriers (like required wash and disinfectant) preclude likely transfer. I’d suggest that we all take time to critically reexamine that assumption; because right now, the entire world’s scientific consensus regarding H5 transmission in dairy cattle continues to rest on something similar to this happening, based on USDA’s narrative for H5 infection and transmission. This required ascending transmission is the part that we’ve skipped over in our zeal to prove our overall transmission theory.

I remain convinced that H5 is an as yet somewhat poorly adapted respiratory virus in cattle as well as other mammalian species that is very well adapted to mammary tissue if it gets there systemically. IF scientifically verified natural transmission of ascending virus from either the environment or the milking claw is demonstrated and replicated, I’ll reconsider; otherwise, we’re way out on a limb claiming this as the main or only route of transmission.

John