Ohio H5N1 Poultry Disaster Continues

15 Flocks - 2 million layers and pullets, 12,600 ducks, and 11 turkey flocks confirmed this week to date

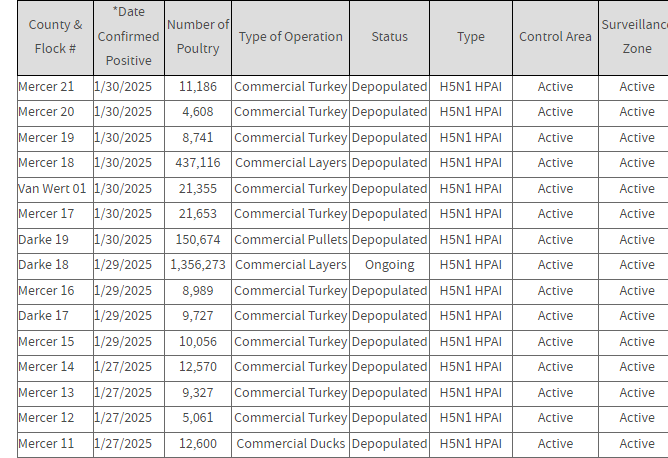

Ohio Department of Agriculture does an admirable job of posting in near real-time a list of confirmed H5N1 infections in commercial flocks within the state: Poultry | Ohio Department of Agriculture. Here is an updated table showing 15 newly confirmed H5N1 flock infections this week since I wrote about this last weekend: While Layers are Dying, Are We Going to Feed our Seed Corn?

I added these 15 new flocks to the table from last weekend’s post to arrive at updated losses just in 2 counties in Ohio in the last month+ from H5N1:

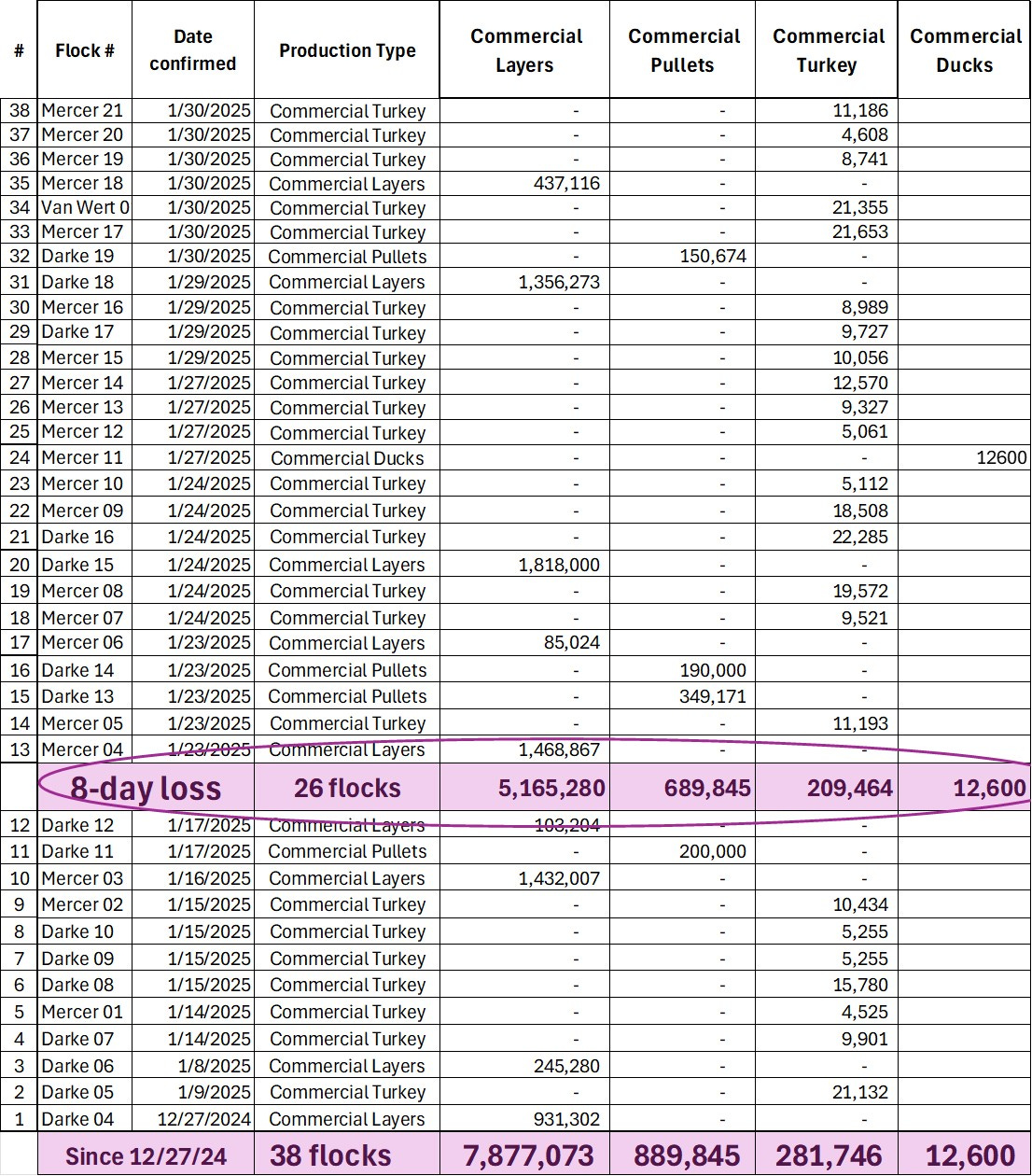

26 flocks in 8 days - 5.16 million layers, 0.69 million pullets, 209 thousand turkeys, and 12,600 ducks! (now in 3 counties)

38 flocks in 34 days- 7.88 million layers, 0.89 million pullets, 282 thousand turkeys, and 12,600 ducks

According to the 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture, Mercer and Darke Counties had total layer inventory of 14.4 million head of chickens; the area has lost over 50% of its layer population to H5N1 HPAI in 34 days! (the Census data does not have turkey inventory data as readily available).

It’s really difficult to overstate the magnitude of outbreak on the local area suffering through this. It’s emotionally and financially devastating to all associated in any way with the poultry industry, including those businesses serving the infra-structure. I’m poorly qualified to comment further on all the pain and financial losses being endured here, but we must not lose focus on the human and animal suffering as we analyze the disease outbreak itself.

Turning to the scope of this outbreak as an “armchair” population epidemiologist, this is the type of disease explosion that cries for a mass investigation with widespread information exchange. 31 flocks in 33 days across 2 counties does not suggest a simple wild bird spillover alone to me, assuming even basic biosecurity protocols are practiced by affected premises. Genomic analysis of each new outbreak is critical in assessing possible sources of infection. Unfortunately, that information is not being shared for public review. We don’t even know the likely clade of the latest isolates, although I have heard reports that earlier Ohio isolates were clade D1.1. Regardless, questions remain why this 2-county area has such a concentration of new cases in such a short period of time.

Similar to H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 in dairy herds in California and earlier in Colorado, Idaho, and TX, I think we need to consider the likelihood that we have a large area build-up of infectious virus in one or more species (domestic and wild) in the area leading to the poultry outbreaks. We are certainly finding it successfully in poultry, given its high mortality, awareness, and indemnity provisions. I assume we may be also looking in peridomestic species near affected flocks, although reporting of those results is much slower. I also hope that human monitoring is ongoing in farm and depopulation workers on all the affected farms and at area clinics and hospitals. I’ve seen no reports of human illness from western Ohio, and we all pray it stays that way.

My biggest concern relates to the lack of evaluation in likely susceptible livestock species in the heavily infected 2-county area. We know that other species of domestic livestock are highly likely to be susceptible to H5N1 2.3.4.4b of either prevalent strain (B3.13 or D1.1). Frankly, we should already have had preliminary clade D1.1 direct infection studies completed in cattle, pigs, sheep, and cervids, given the time we have known that this virus is prevalent in the environment and infecting animals in North America. However, that basic research work has been suppressed.

We will likely have to discover new species susceptibilities by accident and personal field veterinarian and diagnostic lab clinician courage, much as we did with H5N1 in dairy cattle. I’ve already heard too much chatter of producers in multiple industries refusing to test high risk animals for fear of diagnosing H5N1 or reassortants through sequencing.

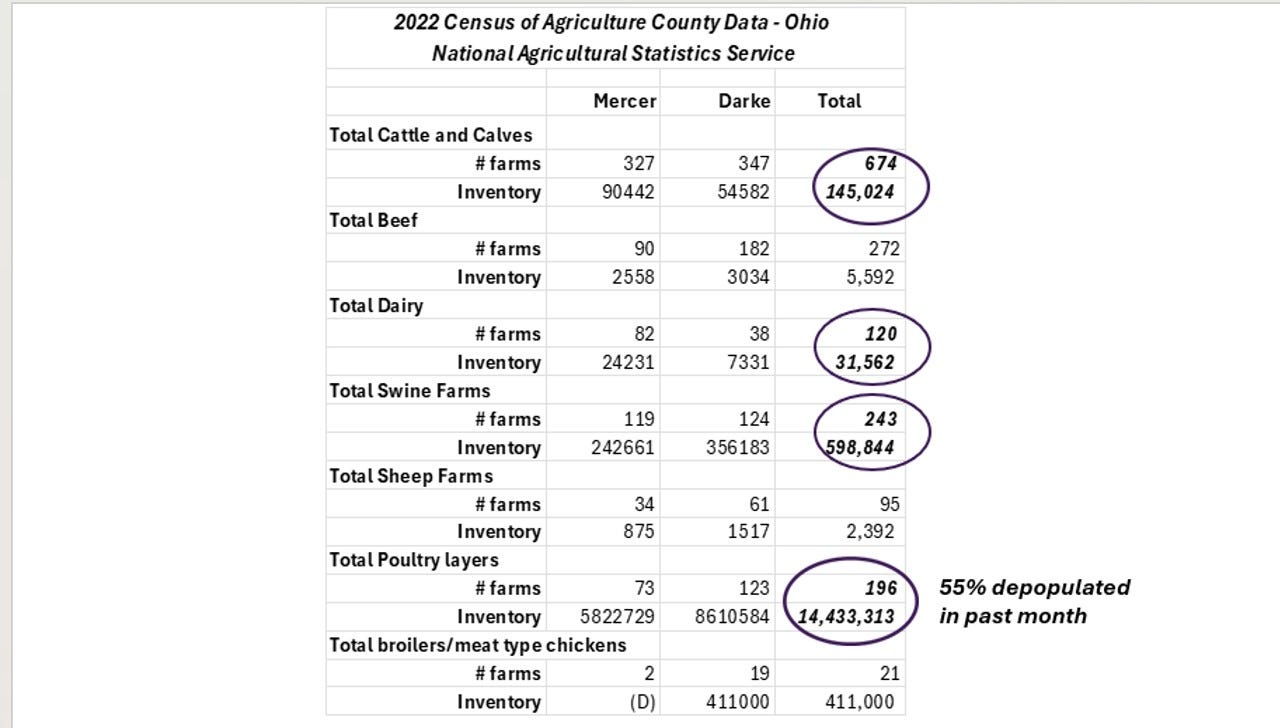

Western Ohio is a prominent agricultural production area for multiple livestock commodities. I accessed 2023 NASS Census Data for the 2 counties hard hit by the avian influenza outbreak:

2022 Census of Agriculture County Data Ohio USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service

Mercer and Darke Counties have lost 55% of their layers in a little over a month, with a total of about 9 million birds dead or depopulated. That is a huge amount of viral shed, even with prompt depopulation. However, those 2 counties also contained (as of 2023) 674 farms with 145,000 cattle and calves, of which 120 are dairy farms with a total of 31,500 dairy cows. There were also 243 hog farms with nearly 600,000 pigs on inventory.

Does it make any sense to heavy surveil the area poultry populations, but ignore 750,000 cattle and swine on 900 farms in the same 2-county area? We certainly shouldn’t check every livestock farm in both counties; however, what about larger production units (“virus magnets”) within control and/or surveillance zones of infected poultry facilities?

“Something” is greatly magnifying H5N1 in western Ohio. It may just be the poultry population. It may include a large wild bird-wildlife component. Or it may also include a domestic livestock infection, much as earlier happened in Colorado and other states and later in California and Utah. We’ll never make progress in slowing bird infections if we don’t understand ALL the true infection reservoirs.

Nobody “volunteered” western Ohio to be ground zero for studying potential H5N1 interspecies spread; however, it appears to me that circumstances have perhaps given it that opportunity. I believe that leadership in moving this knowledge forward will need to come from state and local initiatives and research, given current paralysis at the federal level in both animal and human health leadership. The good news is that there is plenty of capacity to do that in the Buckeye state. They’re National Champs!

John