Federal Infrastructure Devoid of Pandemic Preparedness as We Choke Our Basic Research and Development Funding

Remember when we all said, "At least we have Jerry Parker?" Well, now we don't...

STAT is a subscription only health-related news service, well-worth the subscription price. On July 30th they posted an exclusive regarding the departure of Jerry Parker from the Trump Administration, written by Katherine Eban of Vanity Fair. Katherine graciously posted the exclusive article in its entirety in her recent LinkedIn post.

Quoting Katherine’s post directly:

My latest exclusive: The Trump Administration's pandemic preparedness leader Gerald Parker has resigned and biosecurity expertise is flatlining at the White House, I reported in STAT.

The White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy has no leader and zero staff. The National Security Council's biosecurity directorate has no leader and only one part-time staffer left. For months, Parker was stymied by the White House in his efforts to staff up the NSC directorate. Trump is "inviting catastrophe," Sen. Patty Murray told me.

By the time he departed last week, Parker had no dedicated admin staff and was unable to bring on additional officials. “It was impossible to man the light tower. He was sitting next to the light tower when it’s off,” a person familiar with the situation put it.

The White House called the claim of diminished biosecurity expertise "fake news."

You can read the story here:

https://lnkd.in/ee3EXgHf

Many of us with backgrounds in One Health were relieved when Dr. Jerry Parker, an experienced veterinarian and former commander of the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases would be leading pandemic preparedness efforts in the current administration, supposedly as head of the Office of Pandemic Preparedness. However, quoting the STAT article:

…In recent weeks, according to officials who spoke with STAT, Parker resigned after roughly six months — and was never actually appointed the formal head of the pandemic preparedness office in the first place. The White House, the officials said, had never corrected earlier reports that it had appointed him to that office, one Trump had threatened during his reelection campaign to close.

Instead, Parker had been serving as the head of the biosecurity and pandemic response directorate within the National Security Council, according to the officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity. As the pandemic preparedness office dwindled, he inherited some of its work and supervised a staff member and had spent months trying to build up his NSC directorate.

Both the biosecurity directorate and the Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy are currently leaderless. The former has one part-time employee, and the latter has no remaining staff — a sign that the White House has minimal biosecurity expertise, at a time when the country faces myriad biological threats and the ever-present threat of another pandemic.

“There is no state of coordinated national preparedness,” said a former Biden administration biosecurity official, speaking on condition of anonymity to talk candidly. “We are flying blind, and there is nothing organized at the White House to protect us. We can’t detect, we can’t protect, and we would certainly respond later than other countries” should a pandemic occur….

In its statement, the White House spokesperson said STAT’s assertion of diminished expertise was erroneous and that “the Biosecurity and Pandemic Response portfolio has been moved to the Homeland Security Council.” A January presidential memorandum specified that a single staff would serve both the National Security Council and the Homeland Security Council.

As several officials explained, the biosecurity directorate is not staffed or functional, regardless of where it sits on the organizational chart.

According to Wikipedia, The Homeland Security Council (HSC) is an entity within the Executive Office of the President of the United States tasked with advising the president on matters relevant to homeland security. The current homeland security advisor is Stephen Miller. Given the current administration’s all-consuming objective for illegal immigration deportations under Mr. Miller, a lack of focus on pandemic preparedness and response by this executive unit is not surprising.

My March 30 column reported on STAT coverage of the “reorganization” of ASPR within HHS:

…Established to respond to national disasters from Hurricane Katrina to infectious disease outbreaks, ASPR has worked for two decades as an independent division within HHS, collaborating across the health, defense, and homeland security departments. It includes the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, which finances the development of new biomedical technology and played a crucial role during the Covid-19 pandemic….

BARDA will now be combined with a President Biden-founded agency under a new “Office of Healthy Futures,” according to two people familiar with discussions happening Friday. The decision cleaves the biomedical group from its emergency response agency, which will be shuffled into the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention…

So, CDC theoretically gained some emergency response capabilities from ASPR in the reorganization to add to its epidemiological support functions and zoonotic expertise, but it lacks clearcut response authority and a tested leadership structure for pandemic response.

Finally, most of us have read of the confusion regarding the status at FEMA, the other national emergency response organization outside of the National Guard and military. I hope and pray that we will not be forced into military rule in the event of a national health emergency; however, a degraded pandemic emergency response infrastructure combined with an overwhelming infectious agent pandemic could well drive us into some very perilous times. If we are forced into triage-type health care rationing by lack of adequate volume or distribution of needed resources, someone will have to make allocation decisions. It may take the military to enforce those choices. A pandemic could have dire governing consequences beyond what we can currently imagine.

Let’s all hope and pray that we stay lucky with the zoonotic viral lottery, doing all we can to demand effective pandemic and all hazards response structures at all levels of governance. This level of neglect cannot prevail. We’re better than this!

Longer Term Scientific Prowess is also Degrading

An article in The Atlantic this week really resonated with me as a “Sputnik kid”. I’m just old enough to remember the U.S. paranoia from the Soviet satellite and the resulting push to the moon. We were all lucky, because that fear drove the “space race”, which in turn financed (government taxes!) some of the greatest scientific advances known to man. From the late 1950’s on, U.S. government policy has included significant investments in basic and applied scientific research. Actually, as an Iowa farm kid, federally funded research benefited me personally and the country as a whole through ag research support, which actually took root much earlier. ARS predecessor research dates back to the establishment of USDA in 1862.

We now are once again at a crossroads, where a significant part of our society fervently believes that research money is “wasted”, better retained by taxpayers or utilized to meet existing bedrock government obligations like Defense, Social Security and Medicare. While federal funding for science has always been a challenge, this is the first administration where recissions of existing funding and wholesale abandonment of government research funding and staffing cuts, particularly in health sciences, has been seriously enacted at very significant levels.

This Atlantic article provides a long-term historical context for not assuming that ongoing national support for scientific is a given. My lifetime has marked an uninterrupted period of U.S. federal support scientific research; however, that is not necessarily a given:

The Atlantic: Every Scientific Empire Comes to an End

…The very best scientists are like elite basketball players: They come to America from all over the world so that they can spend their prime years working alongside top talent. “It’s very hard to find a leading scientist who has not done at least some research in the U.S. as an undergraduate or graduate student or postdoc or faculty,” Michael Gordin, a historian of science and the dean of Princeton University’s undergraduate academics, told me. That may no longer be the case a generation from now.

Foreign researchers have recently been made to feel unwelcome in the U.S. They have been surveilled and harassed. The Trump administration has made it more difficult for research institutions to enroll them. Top universities have been placed under federal investigation. Their accreditation and tax-exempt status have been threatened. The Trump administration has proposed severe budget cuts at the agencies that fund American science—the NSF, the NIH, and NASA, among others—and laid off staffers in large numbers. Existing research grants have been canceled or suspended en masse. Committees of expert scientists that once advised the government have been disbanded. In May, the president ordered that all federally funded research meet higher standards for rigor and reproducibility—or else be subject to correction by political appointees…

The article cites numerous examples over the centuries of government interference and outright aggression towards brilliant scientists, e.g. all the Jewish refugee scientists from Germany that assisted in the U.S. effort in World War 2. It’s a sobering read. I’d hope that the trends can be reversed here in the U.S. soon to minimize the damage; however, it’s difficult to move relocated senior scientists back after repeated mistreatments and loss of support and academic freedom.

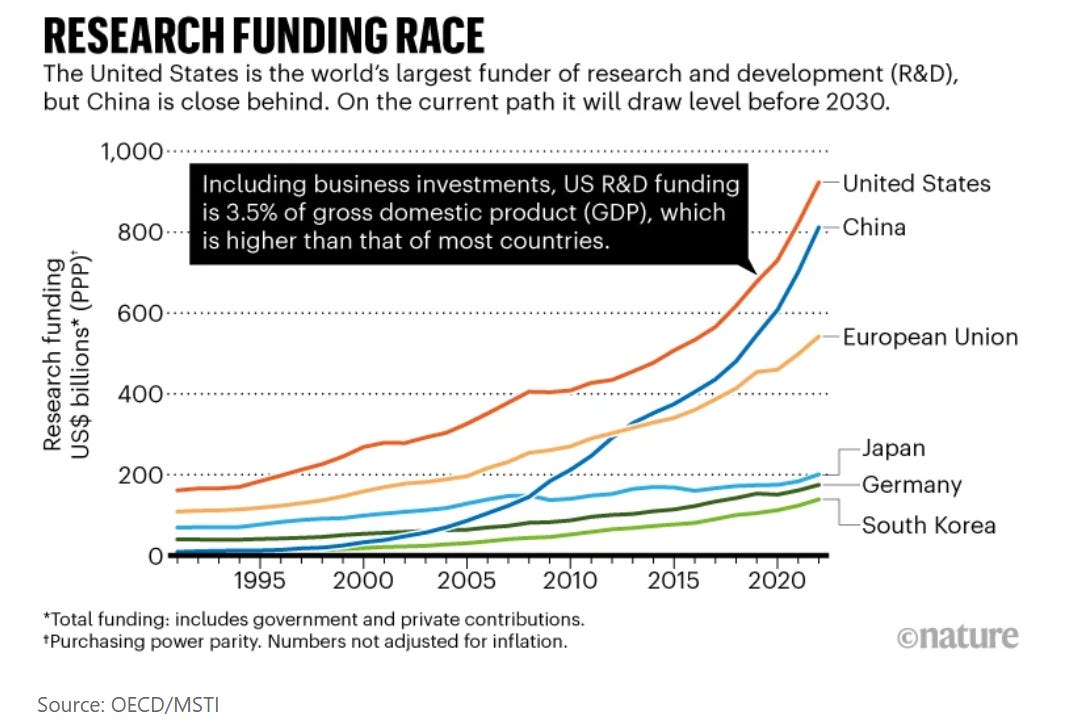

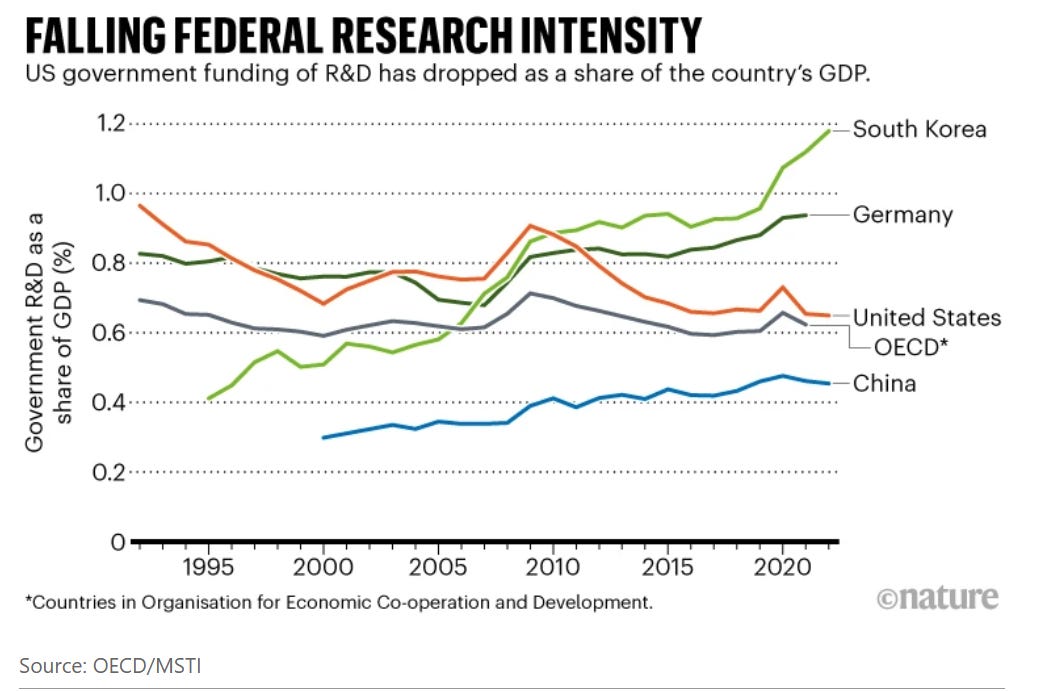

Even before the events of 2025, the U.S. support for scientific research has been concerning. An article from Nature, citing OECD/MSTI data showed the following graphics:

While our total research funding (government and private) continues to grow in total dollars, the government share as a percentage of the GDP has fallen from a peak in 1992 of about 0.95% to 0.65% in 2022. It would be interesting to see where that number might land if all of the proposed budget cuts in 2025 are baked into the estimates for future years. Also note that we are barely higher than the average for all countries in the OECD, and Korea invests twice as much of its GDP in R and D as does the U.S.

What will we lose if we no longer dominate? Ross Anderson in The Atlantic states:

If the U.S. is no longer the world’s technoscientific superpower, it will almost certainly suffer for the change. America’s technology sector might lose its creativity. But science itself, in the global sense, will be fine. The deep human curiosities that drive it do not belong to any nation-state. An American abdication will only hurt America, Shapin said. Science might further decentralize into a multipolar order like the one that held during the 19th century, when the British, French, and Germans vied for technical supremacy.

Or maybe, by the midway point of the 21st century, China will be the world’s dominant scientific power, as it was, arguably, a millennium ago. The Chinese have recovered from Mao Zedong’s own squandering of expertise during the Cultural Revolution. They have rebuilt their research institutions, and Xi Jinping’s government keeps them well funded. China’s universities now rank among the world’s best, and their scientists routinely publish in Science, Nature, and other top journals. Elite researchers who were born in China and then spent years or even decades in U.S. labs have started to return. What the country can’t yet do well is recruit elite foreign scientists, who by dint of their vocation tend to value freedom of speech.

Whatever happens next, existing knowledge is unlikely to be lost, at least not en masse. Humans are better at preserving it now, even amid the rise and fall of civilizations. Things used to be more touch-and-go: The Greek model of the cosmos might have been forgotten, and the Copernican revolution greatly delayed, had Islamic scribes not secured it in Baghdad’s House of Wisdom. But books and journals are now stored in a network of libraries and data centers that stretches across all seven continents, and machine translation has made them understandable by any scientist, anywhere. Nature’s secrets will continue to be uncovered, even if Americans aren’t the ones who see them first.

Do we want to abdicate our leadership in basic research, likely ceding initial applications of those gains to others who may not share our values for freedom and open inquiry? Knowledge is power, and losing the knowledge race will ultimately place our American and Western systems of personal and intellectual freedom at further risk.

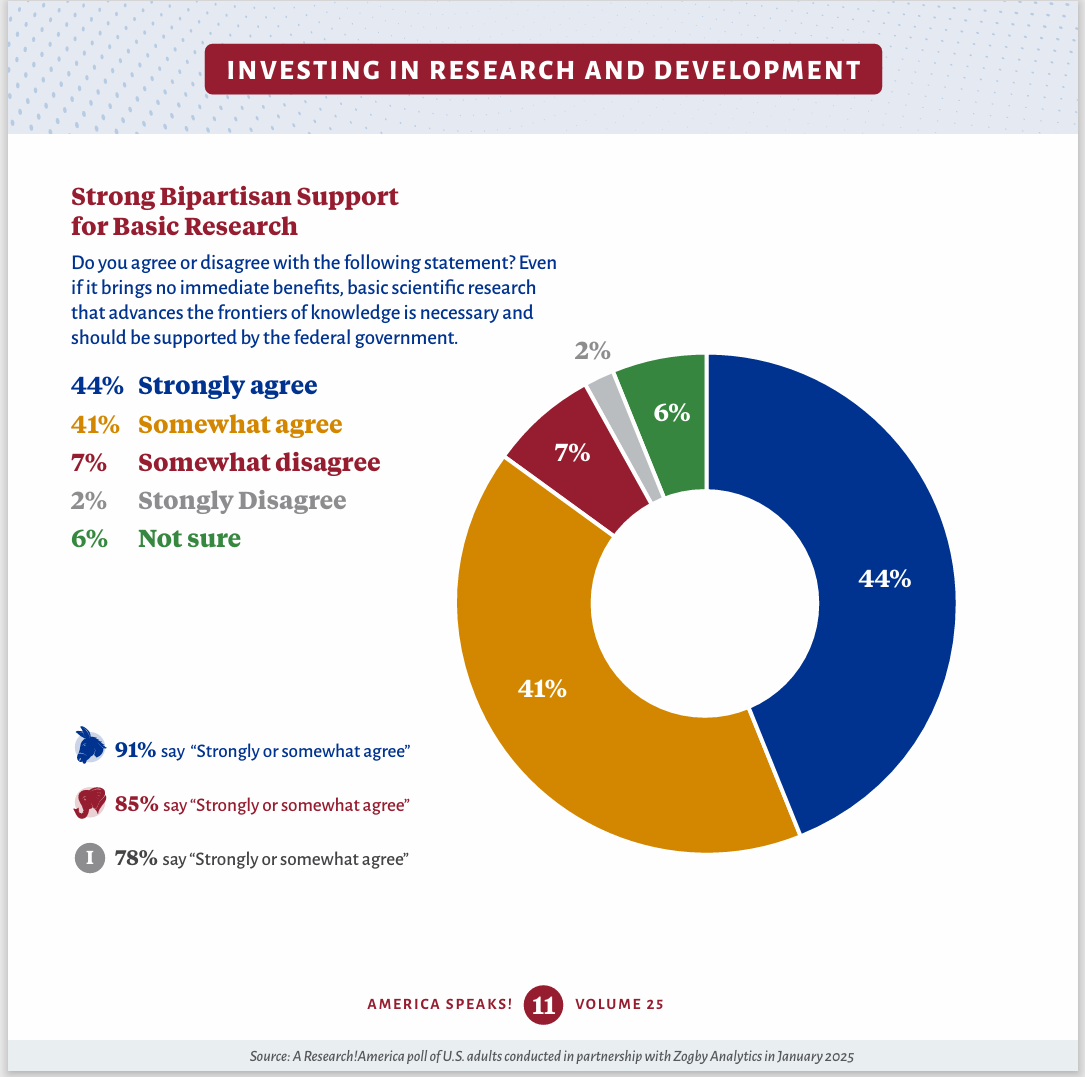

There is some good news to end this column! I came across a post on LinkedIn from the advocacy group: Research!America: Discovery. Innovation. Health. The post links to a survey recently conducted to gauge Americans’ attitudes towards supporting basic and applied research, particularly in health care: Poll-Data-Summary-Volume-25.pdf

The whole survey is very interesting, but I found this reproduction from page 11 very reassuring, with 85% bipartisan agreement that basic research is an important government function:

We currently have a small group of small government idealogues led by Russell Vought at OMB and other zealots like Stephen Miller and RFK Jr. with twisted ideologies running roughshod over both pandemic preparedness and scientific R and D. I’m confident that neither a broad swath of Congress nor the heart of America will long countenance these outrageous turns of events. We all need to keep speaking up, pointing out the obvious, and stay ready to respond collectively if the worst happens.

John