H5N1 Dairy Infection Narratives and Promises Slip Further Away

The mechanism of transmission within and between dairy herds is a critical question that remains and urgently needs to be answered….

All of us in the scientific community pride ourselves in following the evidence wherever it may lead us in our fields of expertise. We intuitively understand that persisting in fitting a preferred paradigm to a major question only discredits our reputations as evidence mounts for contrary findings.

For well over a year now the national and world regulatory establishment as led by USDA/dairy industry collaboration has maintained the theory that the primary means of cow-to-cow transmission of H5N1 2.3.4.4b B3.13 virus is through contaminated milking equipment and fomites passing virus upward via the teat canal into the udder parenchyma. While conceding that the virus may transiently be found elsewhere (lungs, urine, blood), under this hypothesis, the clinical mastitis and copious amounts of virus produced in infected quarters provided sufficient evidence that H5N1 in dairy cattle is primarily a lactating cow infection, unlikely to significantly spread beyond lactating cattle. Under these assumptions control and eradication is possible through isolation, increased biosecurity, and recovery of the herd (exhaustion of infection). Importantly, the agent provides little or no risk to non-lactating dairy or to beef cattle with this primary infection route.

I’ve written extensively regarding the holes I see in this paradigm, and explosive multi-state outbreaks over many months, extending into poultry flocks as well as involving other H5N1 strains (D1.1) in dairy cattle, poultry, and humans have added to the evidence for a much more complicated picture.

This week Michael Coston with Avian Flu Diary dug up a new preprint poking more holes in the milk-udder transmission theory. Please read both Michael’s entire column as well as the entire paper he reviews. Both contain a lot of wisdom for consideration.

Today we have a preprint (albeit sporting an excellent pedigree, including Andrew Bowman & Richard Webby), which challenges the current hypothesis that bovine HPAI is being spread primarily by contaminated milking equipment. While they confirmed that Bovine (B3.13) H5N1 efficiently infects the bovine mammary gland at very low infectious doses - and produces clinical disease and reduced milk production - they were unable to duplicate the spread of the virus via contaminated milking equipment under controlled experimental conditions.

Here is the link to the paper itself: Dairy cows infected with influenza A(H5N1) reveals low infectious dose and transmission barriers

Abstract

The discovery that highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus exhibits a strong tropism for the bovine mammary gland1–4 represents a major shift in our understanding of influenza A virus host range and tissue specificity.

We conducted a comprehensive series of experimental studies with influenza A(H5N1) B3.13 genotype in lactating dairy cattle to address several key questions related to the viral dose required to establish infection, routes of exposure that lead to transmission, and factors contributing to the morbidity and mortality observed on farms. We demonstrate that intramammary exposure to as few as 10 TCID50 is sufficient to establish robust infection, shedding of high viral titers in milk, and clinical mastitis.

Despite evidence of such a low infectious dose, we were unable to recapitulate transmission to sentinel cows via contaminated milking equipment and close contact with infected animals under experimental conditions. High-dose intramammary exposure to influenza A(H5N1) drives severe clinical outcomes and mortality observed in dairy cows on-farm, while respiratory and oral exposure are less likely to establish productive infection and associated morbidity.

This study challenges current hypotheses of influenza A(H5N1) transmission on dairy farms5,6, raising important questions about potential agent, host, or environmental cofactors that contribute to the spread of the virus.

(SNIP)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that a low dose of virus is sufficient to establish robust intramammary infection, which may underlie the widespread and efficient transmission of influenza A(H5N1) in dairy herds.

However, sentinel cows repeatedly exposed to contaminated milking equipment and cohoused with infected cows did not become infected, indicating that cow-to-cow transmission observed on dairy farms may depend on factors that are not easily replicated under experimental conditions in high biocontainment research settings.

(SNIP)

Although human-to-human transmission of influenza A(H5N1) virus has not been reported, the persistence of the virus in dairy cattle and evidence of mammalian adaptation, coupled with the broad and unprecedented host range, are alarming from a public health perspective. A second, separate introduction of the D1.1 genotype virus, primarily circulating in wild birds, was reported in dairy cows in early 2025.

Unlike the B3.13 virus circulating in cattle, this D1.1 genotype has been associated with severe disease in humans, resulting in two deaths31–33—a highly concerning feature should this genotype continue to spread unfettered.

Further, the co-circulation of B3.13 and D1.1 viruses in dairy cows increases the risk of reassortment and viral evolution and complicates efforts to control the influenza A(H5N1) outbreak. Additional studies are needed to characterize the immune response and assess the level of protection following re-exposure to both homologous and heterologous influenza A(H5N1) viruses. The mechanism of transmission within and between dairy herds is a critical question that remains and urgently needs to be answered….

Michael then adds the following in his column:

The fact that we are now 15 months into this crisis and still don't have a solid understanding of how the HPAI virus is transmitting among dairy cattle should give all of us pause.

Testing of cattle remains limited and is often at the discretion of the farm owner, many of whom are reluctant to cooperate over fears of economic losses, and the stigma of quarantine.

We've also seen farm workers reluctant to report illnesses, or refuse to be tested, over fears of losing their jobs (see EID Journal: Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus among Dairy Cattle, Texas, USA) or of an encounter with immigration officials.

Reporting has slowed to a glacial pace, making it very hard to know exactly where the risks from H5N1 currently stand.

While we've been lucky so far - and bovine H5N1 hasn't sparked a large-scale human outbreak - these viruses continue to evolve along numerous pathways, and what emerges tomorrow, or next year, may not be so constrained.

Should that day ever come, we'll rue all of the days we squandered while we optimistically waited for the virus to `burn itself out'.

While this paper pretty well laid to rest the udder transmission narrative, it did no favors for my favored H5N1 transmission narrative(s) either. Researchers, including this group have been unable to reliably transmit virus at a level to produce clinical illness from infected to naive cattle under BSL-3 conditions by close contact. So definitive mechanism(s) or conditions for efficient viral transfer continue to elude lab reproduction, despite occurring so easily in the field both within and between infected herds.

Perhaps the most definitive, but rarely documented transmission work we possess comes from field case work, with a paper released recently by Lombard, Stenkamp-Strahm, McCluskey, and Melody: Early Release - Evidence of Viremia in Dairy Cows Naturally Infected with Influenza A Virus, California, USA - Volume 31, Number 7—July 2025 - Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal - CDC

Abstract

We confirmed influenza A virus (IAV) by PCR in serum from 18 cows on 3 affected dairy farms in California, USA. Our findings indicate the presence of viremia and might help explain IAV transmission dynamics and shedding patterns in cows. An understanding of those dynamics could enable development of IAV mitigation strategies.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that a percentage of lactating cows on dairies affected by H5N1 virus experience viremia before or during the peak of clinical cases in the herd. We detected viral RNA in serum of each PCR-positive cow at a single sample date. Viremia therefore appears to be transient, but the duration is unknown because cows were not sampled daily. Although the finding of viremia does not specify how IAV made it to the bloodstream, virus present in circulation suggests that multiple exposure pathways might be possible, including oral and respiratory routes. Intramammary inoculation studies have shown viral RNA to be in multiple tissues at necropsy (6,7), although viremia had not been consistently detected.

Viremia enables virus to reach many tissues in the body, including the kidneys, which is evident in this study given detectable RNA in urine samples. That process raises concern for food safety and whether viremia could lead to the presence of H5N1 virus in meat from culled dairy cows. A study that evaluated condemned carcasses found viral RNA in 1 of 109 total samples (8). Further, an aborted fetus from farm B, not from a known viremic cow, was positive for H5N1 virus in lung and brain tissue by PCR and immunohistochemical staining. H5N1 virus can move into the reproductive tract and is associated with abortion, which also has implications for the use of fetal serum products. All cows in this study had IAV detection in serum and milk, so it is unclear whether intramammary infection led to viremia or viremia led to intramammary infection. Three cows classified as healthy had viral RNA detected in serum, and 1 of the 3 had viral RNA detected in serum and urine. The relationship between viremia and clinical signs is therefore unclear, although we might have sampled those cows before the onset of clinical disease…

In summary, findings of IAV in serum of cows on farms in California indicates the presence of viremia and could help explain viral transmission dynamics and shedding patterns in cows. Understanding such dynamics could help in development of mitigation strategies to prevent transmission and spread of IAVs, including H5N1 virus.

Something critical is missing in the ecology of the BSL-3 lab which seems to protect naive animals from clinical infection versus what occurs in the field. It could be animal density, total animal volumes (both infected and uninfected), less than optimal environmental temperatures and humidity for transmission, some sort of typical on-farm social contact that is missing in the BSL-3 environment, or some other unknown factor(s).

We need multiple replications of daily observations on incubating farms combined with daily representative environmental, nasal, oral, and serum sampling to make progress on the transmission questions. This may be more difficult to accomplish now that we lack the “epidemic outbreaks” we endured in the past. It’s important that any “naive” farms (no prior infection immunity) identified via bulk tank positive samples be recruited as volunteer study farms to capture this type of data prior to a full clinical outbreak in the herd. Ideally industry and government would collaboratively provide epidemiological “strike teams” poised to assist local veterinarians in outbreak management and response. Once again, quoting the featured Webby-Bowman et al paper- The mechanism of transmission within and between dairy herds is a critical question that remains and urgently needs to be answered.

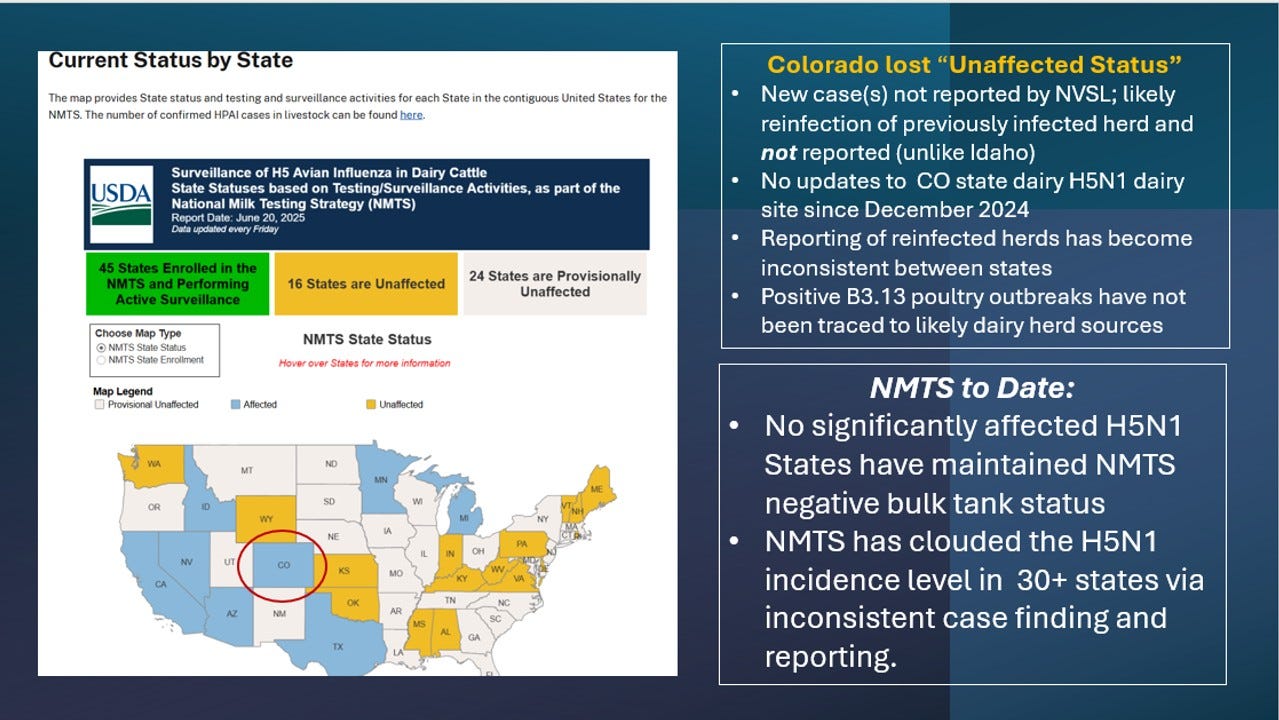

Colorado Now NMTS “Affected”

One piece of news I want to add is something that to my knowledge no one has bothered to report - Colorado apparently has had 1 or more positive bulk tank tests and has moved from an “Unaffected” to “Affected” State on the National Milk Testing Strategy Map:

In the past “re-infected” Colorado herds have not been reported on the NVSL case list and is not this time either. However, the state previously reported them on their state website. Currently their last CO H5N1 dairy update is December 27, 2024, showing all 64 infected herds as “quarantine released”.

My main overriding concern without pointing fingers at any single state or the USDA is that new case reporting has become extremely muddied and inconsistent between states. I personally consider that a herd returning to positive bulk tank status should be a “new case” if the herd had initially become truly negative (CT>=40) for 3 weeks or more. CO has reportedly used a CT cut-off of 35 in the past to avoid “nuisance” positives” cycling in and out. Idaho has recently reported new positives as new cases; Minnesota and Michigan have not as I understand it. California and Texas are uncertain, and New Mexico reportedly had some high-CT non-negative bulk tanks but has not classed them as positive. Then, as I mentioned last week, we have 2025 USA-labeled H5N1 B3.13 poultry outbreak phylogenetic submissions that by default must have originated in a state not reporting any positive dairy herds.

We have “great news” that California and Arizona are the only 2 states reporting new H5N1 cases in the last 30 days! Except, somehow Colorado also lost “unaffected” status, but with no reports of an infected herd. And chicken flocks somehow became B3.13-infected somewhere in the Midwest without infected dairy herds being identified as the source(s) of their demise. The USDA H5N1 livestock line list is becoming less and less meaningful as states label rebreaks as NMTS status changes or fail to identify new cases tied to poultry outbreaks.

The new Arizona case listed this morning is worth a mention since this is the 5th case (likely found via bulk tank testing?) in the state this year:

All cases are likely D1.1 genotype, as was announced in the initial AZ case as a “third wild bird spillover” by USDA (with the NV outbreak being the second). AZ ag officials unofficially communicated with the Maricopa County AZ poultry flock ownership that their initial HPAI infected layer flock was a likely D1.1 genotype spill-over infection from a neighboring dairy infection.

We continue to have good evidence that both the B3.13 and D1.1 strains persist in infected herds and spread onward to new herds and to poultry flocks via unknown mechanisms despite assumed best efforts to contain spread with quarantines and increased biosecurity.

FSIS yesterday announced an extension of testing requirements for culled dairy cows for H5N1 virus in selected carcasses until September 30, 2025, with a plan to test a total of 800 carcasses: FSIS Notice 15-25: H5N1 Influenza A Dairy Cow Testing Program. The results to date are posted HERE:

As of June 11, 2025, FSIS has results from 582 diaphragm muscle samples. Of these, samples from one (1) dairy cow, as well the kidney from that animal, indicated a positive for H5N1 Influenza A at very low levels. Additional sampling from that carcass, including several different types of muscle tissues that correspond to common retail cuts of meat, did not detect H5N1 Influenza A virus. The positive dairy cow carcass was from a processor in California and, consistent with all animals subject to FSIS H5N1 testing, was held pending results and did not enter the food supply. USDA remains confident in the safety of the meat supply.

Readers will recall that this single positive sample occurred early on when the California outbreak was active. It’s reassuring that no further positive dairy cattle carcasses have been identified with an apparent lack of acute herd outbreaks nationally.

New Narratives:

The entire future H5N1 livestock narrative is out of our hands because we choose not to control it! Changes to the virus and where it attacks next will drive the ongoing narrative as a result:

Poultry flocks, especially layers, are the economic pinch point. Will B3.13, D1.X or other strains modify sufficiently, so that 2024 dairy herd immunity fails to attenuate re-outbreaks sufficiently to prevent spill-over to neighboring layer flocks in TX, NM, ID, CO, UT, CA, IA, MN, MI, and other places where B3.13 and possibly D1.X could spill-over from dairy and/or beef feedlots to commercial poultry operations? So far, the dairy infections have been relatively mild in re-infected herds, keeping environmental load down. Will that continue?

Will the virus remain quiescent in beef feedlots and beef on dairy operations? Will those operations provide a transient risk to their workers or to nearby poultry flocks or swine farms? When if ever, will we perform serological testing to assess disease status in non-lactating cattle and other livestock species?

Will the virus stay relatively harmless to people? We keep ignoring a “few” red-eyed and sniffle-nosed undocumented workers who are more determined than ever to avoid routine sampling. What happens if that becomes a dozen kids in a day care with serious pneumonia and hospitalization?

Pigs and reassortment are a risky mix we are failing to address effectively. If the industry really is serious about surveillance, they need to commit to targeted herd surveillance surrounding positive dairy and poultry sites with whole genome sequencing of ALL matrix-positive swine samples (no prescreening with H1/H3 subtyping). What happens if/when we find H5N1 positive pigs despite not targeting them?

Will we continue to intentionally not test wildlife and the environment in real time for H5, while claiming we understand good biosecurity? We now have a virus that is more or less endemic in our wildlife; yet we refuse to utilize our testing capabilities for risk assessments and real-time monitoring in high-risk areas.

Those are 5 potential narrative drivers I see among many more possibilities. I personally don’t expect any proactive measures near term, only reactive ones as the H5N1 virus itself continues to drive the conversation.

Hang on, each week is a new adventure! Layer vaccines may be gaining traction; we’ll see...

John

Transmission or not, cows have a complex social life with frequent physical interactions:

https://www.frontiersin.org/news/2020/08/04/grooming-behavior-between-dairy-cows-reveals-complex-social-network/