USDA H5N1 Plan Unveiled, Pace of Flock and Herd Breaks Ease, and D1.1 in Cattle Repeats

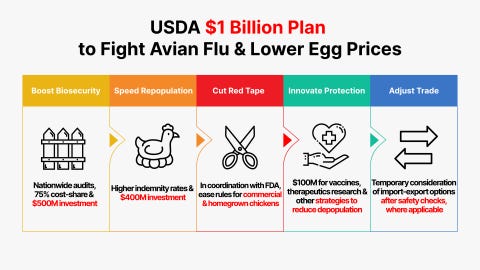

More Commitments to Enhanced Biosecurity and Financial Support for Poultry Producers Plus Commitments for Vaccine Development in $1 Billion USDA Package

I’m a bit late getting my weekly column out this week due to a personal down day, but the good news is that outbreaks in Ohio and Indiana poultry and California dairy and poultry herds continued to slow. Cats cases continue to dribble in. Finally, this morning a new dairy herd was reported in Idaho - a new question now - which genotype- B3.13 (like all past Idaho and CA cases) or D1.1 (like recent NV and AZ herds)? We’ll see. The big news of the week came from the USDA Office of the Secretary. On February26, USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins announced the following:

USDA Invests Up To $1 Billion to Combat Avian Flu and Reduce Egg Prices

USDA’s Five-Pronged Approach to Address Avian Flu

Invest in Gold-Standard Biosecurity Measures for all U.S. Poultry Producers

USDA will expand its highly successful Wildlife Biosecurity Assessments to producers across the nation, beginning with egg-layer facilities, to safeguard farms from the cause of 83% of HPAI cases: transmission from wild birds. These additional safety measures have proven to minimize flu cases; the approximately 150 facilities that follow these protocols have had only one outbreak.

Biosecurity audits will be expanded. Free biosecurity audits will continue for all HPAI-affected farms. Shortcomings for HPAI-affected farms must be addressed to remain eligible for indemnification for future infections within this outbreak. Biosecurity audits will be encouraged and made available to surrounding, non-affected farms.

USDA will deploy 20 trained epidemiologists as part of its increased biosecurity audits and Wildlife Biosecurity Assessments to provide actionable and timely advice to producers on how to reduce HPAI risk at their facilities. These experts will help improve current biosecurity measures to focus on protecting against spread through wild birds in addition to lateral spread.

USDA will share up to 75% of the costs to fix the highest risk biosecurity concerns identified by the assessments and audits, with a total available investment of up to $500 million.

Increase Relief to Aid Farmers and Accelerate Repopulation

APHIS will continue to indemnify producers whose flocks must be depopulated to control the further spread of HPAI.

New programs are being explored to aid farmers to accelerate the rate of repopulation, including ways to simplify the approval process to speed recovery.

Up to $400 million will be available to support these costs for the remainder of the fiscal year.

Remove Unnecessary Regulatory Burdens on the Chicken and Egg Industry to Further Innovation and Reduce Consumer Prices

USDA is working alongside our partners at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to examine strategies to safely expand supply in the commercial market for eggs.

USDA will minimize burdens on individual farmers and consumers who harvest homegrown eggs.

USDA will work with farmers and scientists to develop innovative strategies to limit the extent of depopulations in HPAI outbreaks.

USDA will educate consumers and Congress on the need to fix the problem of geographical price differences for eggs, such as in California, where recent regulatory burdens, in addition to avian flu, have resulted in the price of eggs being 60% higher than other regions of the country.

Explore Pathways toward Vaccines, Therapeutics, and Other Strategies for Protecting Egg Laying Chickens to Reduce Instances of Depopulation

USDA will be hyper-focused on a targeted and thoughtful strategy for potential new generation vaccines, therapeutics, and other innovative solutions to minimize depopulation of egg laying chickens along with increased bio-surveillance and other innovative solutions targeted at egg laying chickens in and around outbreaks. Up to a $100 million investment will be available for innovation in this area.

Importantly, USDA will work with trading partners to limit impacts to export trade markets from potential vaccination. Additionally, USDA will work alongside the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to ensure the public health and safety of any such approaches include considerations of tradeoffs between public health and infectious disease strategy.

USDA will solicit public input on solutions, and will involve Governors, State Departments of Agriculture, state veterinarians, and poultry and dairy farmers on vaccine and therapeutics strategy, logistics, and surveillance. USDA will immediately begin holding biweekly discussions on this and will also brief the public on its progress biweekly until further notice.

Consider Temporary Import-Export Options to Reduce Costs on Consumers and Evaluate International Best Practices

USDA will explore options for temporarily increasing egg imports and decreasing exports, if applicable, to supplement the domestic supply, subject to safety reviews.

USDA will evaluate international best practices in egg production and safety to determine any opportunities to increase domestic supply.

I salute the administration for additional support and a thoughtful review of several areas that may offer help for a very difficult problem. Here are some strong points that I see in the announcement:

Increased biosecurity audits with technical and financial assistance are like motherhood and apple pie! More is always better and will prevent some outbreaks.

Increased paid depopulation support is critical for ongoing compliance, and the willingness to reconsider the rules for faster repopulation is welcome. I’ve felt for many years that HPAI is a relatively fragile virus, and many of the arbitrary rules for down times following cleaning and disinfection may be excessive. This is a good opportunity for federal, state, and industry collaboration to prudently accelerate restocking timelines to be more aligned with actual risk of residual infection.

Utilizing excess (male) hatchery eggs for human consumption and encouraging more homegrown eggs may slightly add to supply, if shown to be equivalent from a food safety standpoint.

Officially encouraging and financially supporting innovative vaccine development is a critical next step for longer term stability against H5N1 for the poultry industry and livestock industry as a whole. Many caveats surround vaccine use, beyond my expertise and the scope of today’s column. We must protect our layer flocks in particular against high levels of environmental H5N1 contamination through raising their natural resistance levels via vaccination.

The concept of more limited depopulations seems to have been fortuitously deemphasized versus the tone of the plan earlier provided by administration economist Kevin Hasset. The plan now states: “USDA will work with farmers and scientists to develop innovative strategies to limit the extent of depopulations in HPAI outbreaks.” Utilizing experienced producers and outbreak veterans in making situationally based partial depopulation decisions adds confidence that this approach will only be applied when all necessary conditions and ongoing monitoring steps are in place to maximize chances for success.

Despite all the positive features of the plan, I also have some reservations regarding unaddressed areas, especially related to potential H5N1 2.3.4.4b reservoirs in domestic dairy and other livestock species. The subject is somewhat covered in 2 sentences: USDA will solicit public input on solutions, and will involve Governors, State Departments of Agriculture, state veterinarians, and poultry and dairy farmers on vaccine and therapeutics strategy, logistics, and surveillance. USDA will immediately begin holding biweekly discussions on this and will also brief the public on its progress biweekly until further notice.

First, we don’t know that dairy cattle are the sole domestic livestock H5N1 reservoir; however, we DO know that they were the source in MOST of the H5N1 B3.13 commercial poultry outbreaks in 2024. The D1.1 genotype from wildlife did not become a huge factor until late 2024.

Now with 10 confirmed D1.1 cases in dairy cattle in 2 states (Nevada-9 and Arizona (1), we may again eventually need to consider spread of avian influenza of multiple genotypes from dairy or other cattle herds back to poultry flocks. Additionally, a closely related D1.2 genotype was isolated from backyard pigs in Oregon, raising the prospect that another farm species could be infected and serve as potential viral sources for poultry flocks.

The poultry plan is silent on the National Milk Testing Strategy, which has shown success in finding the first 2 D1.1 genotype spillovers in Nevada and Arizona testing. Additionally, sporadic B3.13 cases continue to be reported from California as that dairy outbreak burns itself out.

Speaking of Dairy and H5N1

The I-29 Moo University Dairy Webinar Series continued Wednesday, Feb. 26, with Dr. Kaitlyn Sarlo Davila, an ARS researcher, discussing the results of several studies to define the kinetics of protective immunity in cattle infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 2.3.4.4b (genotype B3.13). You can watch the entire webinar via You-Tube on the link above for a good review of ARS research on oral infections in bucket calves with infected colostrum and subsequent immunological studies.

This work now provides researchers with a good reproducible model for orally infecting calves with B3.13 virus, producing a mild upper respiratory disease with consistent nasal shedding and minor lung lesions. This respiratory pathway demonstrated is similar to that found in other mammals with influenza A infections, meaning that many of the infection pathways and processes delineated in other mammalian species likely also apply to cattle infections. Nasal swabs were positive by PCR beyond the 2-day positive milk feeding period, indicating ongoing viral replication in the respiratory epithelium for 5-6 days.

Discussions during the Q and A period turned to National Milk Testing Strategy implementation. Wisconsin, Indiana, and Idaho were just added to the program, leaving only North Dakota, Florida, and Massachusetts unenrolled (Massachusetts is testing negative independently at the Broad Institute, not recognized by USDA as an accredited diagnostic laboratory). Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Mississippi have attained the status of “Unaffected”. CA, NV, AZ, MI, and TX are all “Affected” due to at least 1 positive bulk tank result (either B3.13 or D1.1). The balance of the states (37) has not reported sufficient information to date to be assigned a status. While planned compliance with the program is heartening, it’s really premature to state that we have negative bulk tank surveillance results (in more than 3 states). To my knowledge, no one is reporting number of tests run, sampling representativeness, or the sampling results time lag. These metrics are critical to understanding NMTS effectiveness. It’s unclear whether either the states or USDA have plans to provide that degree of transparency to the public.

Turning specifically to the Nevada D1.1 outbreak, Dr. Alex Turner, VS H5N1 dairy incident commander, reported that 9 herds in the Churchill Valley are now infected, with only the initial herd having showed visible clinical illness. (The AZ herd also was devoid of clinical signs). Virus phylogenetic structures from all 9 Nevada herds are essentially the same (common source), and all display the D701N mutation in the PB2 gene segment. VS has an epidemiologist on site exploring herd links, looking for possible routes of spread. The Arizona D1.1 isolate is NOT closely related to the NV virus and is likely a separate avian viral spillover event.

I’m a bit concerned that on the webinar the prevailing attitude seemed to be that maybe D1.1 isn’t a as big a deal in dairy herds because the cows don’t get so sick. Several reasons for concern still remain in my opinion:

Our n=10 herds in 2 states. We haven’t seen it arise in a full-blown epidemic mode in large multi-flow herds like seen in CA, CO, ID, TX, etc. Hopefully, that won’t happen, but it’s premature to declare this a milder virus.

We had a human case with a D701N mutation in 1 of the first 10 cases- that alone is of zoonotic concern. The D1.1 genotype is thought to possibly be more prone to zoonotic crossover as well as to produce potentially more severe human infections.

In NV with closely located herds, it seemed to spread really easily via some unknown mechanism. How and why?

We have 2 independent spillover events in the first few months of silo testing in “early adopter” states. What will we find when silo/bulk tank testing really gets off the ground in multiple states with higher dairy herd densities and high migrating bird populations?

Finally, a positive herd (dated February 28th) was reported out of Idaho this morning by NVSL; was this B3.13 or D1.1? We’re at the point where that information should be included on the line list, given the differences USDA reports that exist between the genotypes in dairy herd infections.

I wrote a week ago about the Molecular Characterization of the Nevada H5N1 2.3.4.4b D1.1 Dairy Cattle Spillover, which included the human NV isolate plus 4 dairy isolates published by USDA from the first herd(s) reported. The authors did a nice job of utilizing molecular clock analysis to time the spillover event to early December 2024. More sequences may allow further refinement by USDA or others with access to additional isolates.

While these relatively rapid detections point out the value of silo testing for rapid detection of HPAI viral antigen in milk supplies, it also points out the dangers of delay. In this situation, these cows in Nevada weren’t moving. As we discovered last year in other states with dairy B3.13 infections, asymptomatic cattle can move a lot and can spread virus far and wide to additional herds prior to diagnosis.

If we are serious about early diagnosis and prevention of shipping HPAI across herds, we really need to step up testing result turn-arounds! The authors of the article suggest several solutions, but perhaps first we need to accelerate moving from silo testing to farm bulk tank testing, pooling only to the extent necessary to maintain a cost-effective program. Then samples need to be screened locally, at the nearby NAHLN, or even at accredited milk plant labs to eliminate shipping time delays for initial detections.

My overriding concern is that all of our livestock species live within one ecosystem, maintaining a virus that currently is all too capable of passing between them. If we are to get serious about controlling H5N1 in poultry, we obviously need to control it in dairy herds. Even with poultry and dairy vaccination and biosecurity, we cannot allow the virus to flourish unmonitored in neighboring large livestock populations such as beef feedlots, cow-calf operations, and swine herds. Just because a species doesn’t die (poultry) or shed it in milk (lactating dairy cattle), that does not mean that another herd is not contributing to H5N1 viral load in an area. We cannot hope to control risks for any species if we don’t understand the potential viral loads from all species through surveillance of some sort. Our best vaccines in all species will likely be over-run by large viral loads, making integrated area viral control and monitoring strategies imperative.

Finally, we ignore the zoonotic threat at our own peril. We’ve been fortunate to date, but we must slow down the rate at which this virus is replicating in all of our domestic poultry and mammals. We know about the poultry because they die. We’re learning about lactating cows through NMTS. We’d better learn more about the livestock beyond dairy because of their potential to affect both regulated dairy and poultry, as well as the people caring for them. D1.1 appears to be another step closer human adaptation than B3.13, making the situation more perilous.

What’s next?

John